The South Downs Way 100

Posted by Ed on June 27, 2023

When I signed up for the SDW100 last autumn, it was never my intention for it to be a fundraising effort. Dad had not even received a diagnosis at that point. But when he passed, I knew that I wanted to use the run to support some kind of a good cause. I settled on the Peace Hospice, the Watford-based charity who provided Dad with daily nurse visits once he had been discharged from hospital and was being cared for at home, and who provided him with a calm, tranquil, medically supervised environment in which to spend his final days.

As the clouds thickened in those final weeks of Dad’s decline, I leaned more and more on running as a means to cope. It was just about the only thing in my life that was structured; everything else—work, my social life, other hobbies and interests—fluctuated wildly through peaks and troughs. But running was something I couldn’t allow myself to lose my grip on.

The result of this steadfastness was that, in April, when I took on the South Downs Way 50 – a 50-mile race from Worthing to Eastbourne along one of Britain’s oldest footpaths, hosted by Centurion Running – I was just about the fittest and strongest I’ve ever been. I sliced 74 minutes off my 2021 time, surprising even myself by reaching the finish line in seven hours and 58 minutes.

But that was really only the training run – a dress rehearsal in preparation for my first 100-miler, the South Downs Way 100. Taking in the entire National Trail, from Winchester to Eastbourne, it’s become an iconic race in the UK trail running calendar, and arguably the south of England’s definitive 100-miler. Taking in a manageable (for a 100-miler) 3600m or 11,000 feet of elevation gain, its long, steady climbs and gradual descents, combined with largely non-technical terrain and stunning, wide-open vistas make it an enticing option for beginners and experienced ultrarunners alike.

Pre-race

As the race approached, I experienced an understandable wave of anxiety about the degree to which I was really prepared for tackling 100 miles.

In the aftermath of the 50-miler, I’d had to take two weeks off running entirely due to an ankle niggle. Whilst I used this time effectively to focus on getting stronger in the gym, it meant I didn’t get as much volume in between the two events as I’d have liked, only squeezing in one proper long run, and even that was only 26km – nothing like the kind of distance my coach had intended for me to run.

But I also knew that success in an ultra depends on so much more than just physical fitness. Mindset is absolutely key, and, without sounding too arrogant, I simply knew there was absolutely no way I was not going to finish this run. It was just not a question in my mind. Experience, too, is important, and with seven fifty-milers under my belt, I’d come a long way in understanding how to interpret the signals my body sends me during a race.

I often think of these signals as the ‘thin end of the wedge’ of primal impulses like hunger, thirst, or fatigue. A low mood, a dry mouth, a hollow feeling in the stomach – these things can tell you so much about what you should be doing to take care of yourself and ensure a successful outcome. The challenge is paying attention to them and acting in response – pulling yourself out of a groove in order to attend to a small problem before it becomes a big one. In ultras, in some sense, this insight is more important than being a good runner. Or perhaps it’s the same thing.

Of course, there are the things you can control – pacing, food and drink, your use of gear and equipment – and then there are the things you can’t: what might broadly be called ‘the environment’ (one thing ultrarunning has helped me realise is that the subject/environment distinction is fundamentally unclear – more on that later.)

A primary concern for this particular event, it became clear in the week or two leading up to the race, was the weather, with temperatures rising to 30 degrees in parts of the country after a long, cold winter and a months-long, very mild not-quite-spring. The exposed Downs, long since cleared of much of their ancient forest coverage, offer nowhere to hide from the baking sun on a hot day, and as Emily and I drove to the campsite just outside Winchester on the Friday afternoon before race day, the stifling heat – which seemed to reach its thick, muggy apex in the late afternoon – got me a little anxious about the pain cave into which I was inevitably going to descend the next day.

I tried to look on the bright side – no need to worry about rain or cold; probably no need to don an extra layer overnight. A crystal clear summer night on the Downs is hardly an ugly prospect, after all. It would just be a matter of getting through the day.

With that in mind, I prepared accordingly. I made sure to carry plenty of sun cream, an extra 500ml of water capacity above Centurion’s mandatory litre, and I wore my Ciele sunhat for extra coverage as opposed to my usual Ugoku cap.

As the skies lightened on the morning of race day, I arose from our tent at 4am and set about taking care of those last final pre-race maneouvres: coffee, breakfast, lubed-up toes and other chafing-prone bits, and a targeted toilet visit. These aren’t the glamorous parts of ultrarunning, but they really can make or break your race. Get them right and many far more unpleasant situations are avoided (more on that later.)

With ten minutes to go, runners headed to the starting pen. Centurion RD James Elson gave us a race briefing, which included a word of warning about the impending heat and some advice about where extra water sources could be found on course. At one point he asked who was running their first hundred, and I was pleased to see dozens of raised hands joining mine.

And then, just like that, it was time to run 100 miles.

Part one – Matterley Bowl to South Harting

I set off at ‘easier than easy’ pace, content to sit as far back in the pack as was necessary to feel completely comfortable. The first few miles of the SDW100 are a circuit on private land around Matterley Bowl – within a few minutes, it was possible to see the entirety of the pack distributed around the curve of the natural amphitheatre. 340-odd runners, each about to experience an epic journey of one kind or another.

What I so love about ultras is you just cannot tell, even for the first two thirds of the race, who is going to prevail and who is going to have a bad day. Experience has taught me that I seem to be better at pacing ultras, and races in general, than most: by which I mean, I tend to be much further back in the pack at the first checkpoint than I am at the finish. (I’ve yet to run an utra where the reverse is true – where I go out fast and fade hard. It’s possibly something I should deliberately experience one day, just to better understand where my limits are.)

On a 100-miler, of course, the time between that first checkpoint and the finish is much, much longer than in other races, which means more time to make a mistake. In order to mitigate this, I had prepared a quite detailed race plan, not so much to dictate my splits as to provide me with ‘guardrails’ within which to operate.

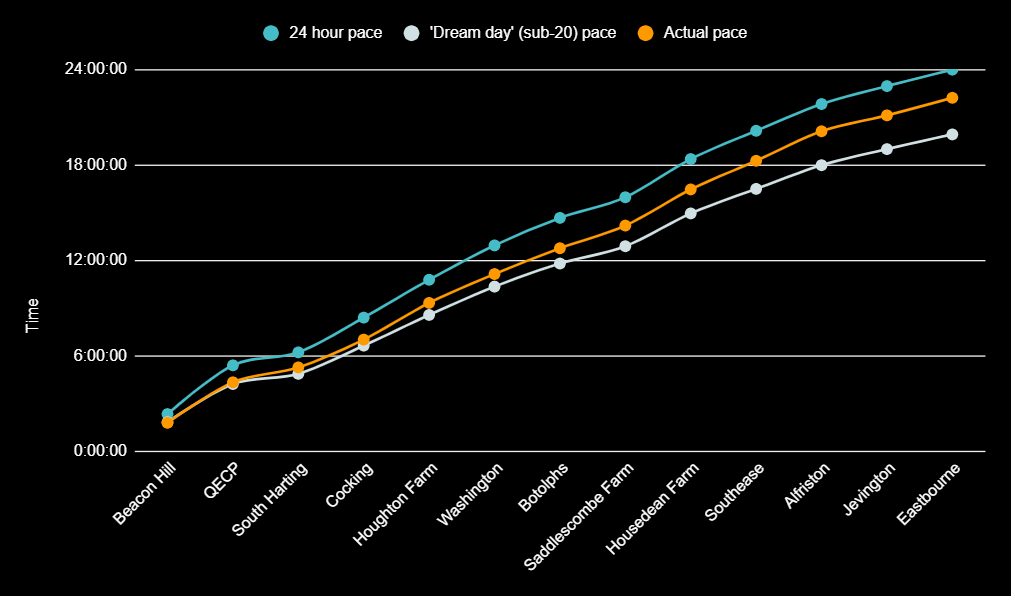

Using a spreadsheet, I mapped out three possible scenarios for the race: ‘dream day’ (sub-20 hours, based on my 7:58 finish at SDW50), 24-hour pace (which I knew I would be chuffed with on my debut 100), and ‘nightmare day’ (chasing the 30-hour cutoff.) I then used evenly-paced splits to calculate checkpoint arrival times for 24-hour and 30-hour pace, whereas for the ‘dream day’ splits I took the average pace and ‘smoothed it out’ a bit, frontloading the first half of the race with a slightly faster overall pace, as I knew would be the case in reality.

This plan was really intended to help my crew, who would be meeting me at a few points after the halfway mark, get a sense of when I would be arriving at certain checkpoints. But it had the added advantage of giving me a really useful way of benchmarking my performance during the race.

For instance, when I got to the first aid station at Beacon Hill, I was three minutes up on ‘dream day’ pace, which told me one thing: despite making every effort to take it easy, I was probably still going marginally too fast. This was useful information, as I was then able to use the next 20 kilometres – the longest gap between aid stations of the whole race – to embrace the opportunity to ease off a little bit. I filled up all three water bottles and headed out within a minute or two, focusing on taking my time.

I really enjoyed this feeling, of relaxing and taking it all in. My running has improved over the last few years to the point where even in a 50-miler I feel like I’m able to ‘push’ pretty much from the off, albeit gently. But in the 100, it was like I was running my first ultra all over again, taking it so incredibly cautiously and conservatively that I actually felt quite relaxed. I got chatting to a couple of different runners, including Darren Strachan, GB Spartathlon runner and one half of London-based Camino Ultra. I took regular walking breaks, even on the flats, and focused on drinking as much water as I could.

By the time I got to the second aid station at the glorious Queen Elizabeth Country Park, 36km in, I was pleased to see that I had been succesful in slowing down, coming in seven minutes shy of my ‘dream day’ pace. Again, I filled up all three water bottles – by this point I’d already drank over three litres in just shy of four and a half hours, and it wasn’t even midday yet – and grabbed some watermelon and orange slices.

My nutrition strategy over the years has reached a fairly consistent approach through much trial and error. Namely: every 30 minutes, with the help of a reminder alert on my watch, I eat a gel, a few ‘blok’ chews, or a handful of sweets/crisps/Mini Cheddars, supplementing all the while with Tailwind; then, at each aid station, I stuff my face with as much fruit, crisps, or chocolate as I can in a minute or two, in the style of Zach Miller. As the race progresses, I’ll add a cup of Coke to the mix at each aid station.

This combination of ‘micro- and macro-dosing’ food seems to really work for me, and I pride myself on having built my gastrointestinal resilience from a state of more or less total non-compliance a couple of years ago to now having essentially an iron gut in ultras. I was of course concerned that, after fifty miles and into unknown territory, that might all fall apart, but there’s nothing you can really do to prepare for that beyond seeing what happens the first time you do it, so I tried not to worry about it.

Leaving QECP I felt strong and motivated, knowing that I was closing in on ‘halfway to halfway’. Whilst the prospect of still having 120km to go was still too much to think about, there’s a lot to be said for ticking off micro-accomplishments during an ultra, and I knew that crossing that first marathon off the list was one such mini win.

I fell into a groove with a pack of runners on the road into South Harting, the next checkpoint. Ultrarunners being ultrarunners, we got chatting about UTMB. At one point, a group of kids on bikes who were preparing for some kind of race lined the road either side of us and burst into spontaneous applause as we passed through. Suddenly it was as though we were running a big city marathon, and our spirits were briefly lifted.

I got to South Harting at quarter past 11 with a comfortable five hour, 15 minute (hilly, off-road!) marathon under my belt. I was by now a healthy 20 minutes behind ‘dream day’ pace, but feeling fresh for it. Despite only having travelled 5.5km since the previous checkpoint, I took the opportunity to down a water bottle and top up all three flasks again. I felt as though I was making good progress, and was already noticing just how many people I was effortlessly overtaking – a good sign, I felt, that I had gone out suitably conservative.

But, as the 50k mark approached, I knew the dreaded ‘endless middle’ of the race was about to unfold before me – no longer in the fresh, early stages, but still too far from the end to think about the finish line. And, of course, the heat of the day was still yet to truly arrive.

Faced with these demons, my focus had to zero in, on processes rather than outcomes. Hydration, nutrition, comfortable pacing – this was to become my world. In my head, two ‘tent pegs’ propped up the foreseeable future – reaching the halfway point (and seeing Emily at Washington a few miles later), and reaching my pacer Mark at Devil’s Dyke, 105km in.

Part two – South Harting to Devil’s Dyke

A few days ago I listened to the Centurion Running podcast recap of this year’s race, in which the hosts speculated that many runners opted to go out faster than usual in a bid to ‘get ahead’ of the warmer weather en route. This spectacularly backfired, and the next aid station, Manor Hill Farm in Cocking at kilometre 56, was the first sign of the shitshow that was to follow that afternoon. A couple of runners were slouched in chairs, glistening with sweat; another was throwing up. There was a general sense that things were getting ugly.

Relatively speaking, I felt quite good at this point – my conservatism was paying off. I’d experienced no internal discomfort, gastric or otherwise, and was comfortably taking in a gel or equivalent every half an hour, supplementing this with fruit at aid stations. Crucially, I was still stopping to pee quite regularly, which I took to be a good sign. But, nonetheless, I took the opportunity to pack my hat with ice (thank you to whoever made sure there was ice!) and drink plenty of water.

All I really recall about the next stretch was the heat of the day truly kicking in, so much so that at times the wind on my face felt like a hairdryer. There are a number of sections of the South Downs Way that are covered by trees, but if you’re heading east, these become more and more infrequent, and the trail instead increasingly consists of exposed ridgelines. I was topping up my sun cream every hour or so, and getting through every last drop of water in between each aid station, even downing half a bottle at checkpoints just to stay on top of hydration.

Coming down the hill into Houghton Farm I had drained all my water supply only to find the aid station was another 500m further along than I’d thought. Even this small unanticipated stretch without adequate hydration was enough for the heat of the day to make itself felt physiologically – I can only imagine how those who had built up a deficit must have felt.

At the aid station – kilometre 74 (nearly halfway) – I dunked my hat in a ‘dunking bucket’ of ice water and again filled up each water bottle. Knowing that I was just 12km or so away from seeing Emily for the first time at Washington, I scampered off quickly.

I got about 100m down the trail before realising that I had zero nutrition on me beside a bottle of Tailwind. It’s hard to believe, but I was genuinely tempted to carry on regardless and suffer through – but the rational, self-observing part of me that is so important in ultras knew that I had to turn around and grab at least a gel or two from the aid station, which I did. All in all I probably lost about one minute (I’d have lost a lot more if I’d have tried to run the next 12km without any food), but it’s amazing just how much your brain can catastrophise such a small mistake.

The next few miles snaked along the valley floor, which was much hotter than any of the sections up on the ridgeline. I was forced to walk much of it, despite it being pancake flat and runnable. As we crossed the River Arun a couple of young guys with whom I had been leapfrogging pointed out a tap by the trail, and we all stopped to soak our hats once more and let the water pour over our frazzled heads, enjoying the heightened simple pleasure that ultras can induce.

Once again, the trail climbed up high, and whilst the sun was no less relentless, there was at least a gentle breeze and less of an oven-like atmosphere than in the valley. It’s remarkable to reflect that at this point I had been on my feet for around 10 hours – two more hours than I ran the SDW50 in – and yet I was not even halfway through the race. Psychologically I was doing pretty well. My mood wasn’t consistently chirpy, but I was yet to experience any properly rough patches, and, occasionally, I was even enjoying myself…!

I’d read somewhere that in order to run a 24-hour 100-miler you need to do the first 50 miles in 10 hours, in order to account for slowing down in the second half. For some reason I’d got this into my head as gospel, so when I passed the halfway point of the race in around 10 hours 20 minutes I panicked that 24 hours was not going to be possible. And yet, doing the maths, the notion that I had over 13 hours to do the next 50 miles felt… completely fine. Knowing that I tend pace myself better than the average runner, I decided to dismiss any concerns and just let the race unfold however it would.

Soon, I reached the turn-off at Washington where the race momentarily leaves the main South Downs Way route. I took a second to enjoy the sign here indicating the halfway point of the official South Downs Way National Trail, which I remembered feeling so elated to have reached in 2018, when I walked the whole trail over the course of a week. Then, it had taken me three days to reach; in the race, just over 10 and a half hours.

On the long descent into Washington, I tried to formulate a plan to take advantage of the upcoming crew points. I had initially planned to pick up a fresh bag of food at Devil’s Dyke, 105km in, but having already run out of food I knew to get that off Emily now. Each of the two bags I’d prepared contained half a dozen gels, some Mini Cheddars, and some Tailwind packets, including a pre-loaded bottle of caffeianted Tailwind. Centurion provides Tailwind at checkpoints, but they dilute it more than I prefer, so I felt like it was a good idea to have my own supply, especially later in the race when liquid calories might be more necessary.

Before I knew it I was in the village and shuffling into the checkpoint, where Emily was waiting by the roadside to greet me. This was the first time, ever, that I’ve had crew during an ultra – it was also Emily’s first time crewing. So we both had to work out a little bit what the best approach was. Something about having an audience really changes things, but I realised quite quickly that giving in to the temptation to stare into the void and feel sorry for myself wasn’t necessarily the most efficient strategy.

I asked Emily to get the first food bag from the car, and whilst she fetched it I helped myself to more fruit and extra water from the aid station, saying hello to volunteer and fellow South Londoner Ally who was chopping up watermelon like a woman on a mission. My focus was, by this point, primarily on my own internal struggle, but I did take a moment to look around and gauge how others were faring. The answer was: not well. Washington village hall during the hottest part of the day was like a warzone, with sunburnt, nauseous, dripping wet runners everywhere I looked.

I realised that, despite feeling like a pile of crap, I was broadly a more put together pile of crap than just about every other runner at the checkpoint. This lifted my spirits somewhat, and after Emily brought me the food bag we made our way back out onto the road.

As we walked, she passed on some of the messages from the WhatsApp group of friends and family who were following along online. It was genuinely lovely to hear that people were invested in my effort, which up until then had felt like a relatively lonely affair. I left the aid station with a newfound sense of resolve, knowing that I was over halfway to the finish line and the heat of the day was about to break. As Emily put it, “The worst part is over now.”

The climb out of Washington was steep and more technical than most of the race, but really this didn’t matter – any incline of more than 0.5% was, at this point, walking terrain. After half a mile or so it joined a road – again largely too steep to run – and as I walked up it, I felt something in the air give way. It was the subtle, barely perceptible ‘turning point’ of the day’s heat, the moment when the temperature stopped rising and started to gently ease off.

It was like being inside a cosmic sigh of relief. Quite suddenly, I felt my attentional focus shift from narrow-beam survival mode to a wide angle openness. I found myself taking it all in – the beautiful Weald to my left, bathing in the stretched evening sunlight, reaching all the way to the North Downs in the distance. Even the road itself was a blessing – soft, gentle concrete caressing my feet. It all got a bit religious.

Soon, I had another reason to rejoice, as the course rejoined the South Downs Way and I found myself on the familiar ground of the SDW50 course. Despite still having over 40 miles to go, the fact that it was 40 miles with which I was well acquainted somehow made it an easier pill to swallow, as though the distance was compressed by my being able to picture what it would involve.

Soon, the familiar sight of a pig farm to my right signalled the beginning of the descent into the roadside Botolphs aid station, the first checkpoint on the SDW50 course. Here, a fast-looking runner was slouched in a chair, looking as though he was paying a price for his efforts. I was also fading a bit, the evening golden hour (and the 98km in my legs) making me feel a bit sleepy. But I was also energised by the sudden feasibility of the task at hand – 60 more kilometres. A long way, sure, but not a crazy long way. It felt like a distance I could handle, one with a number of boxes to tick off as I go – 50k left, a marathon, 20 miles, a half marathon, and so on. This is doable, I thought to myself. I am going to run 100 miles.

Somewhere shortly after the climb out of Botolphs, I watched the distance on my watch tick over to 100km, and patted myself on the back a little bit for reaching triple digits for the first time. Things started to feel like they were moving at a decent pace – I passed the YHA at Truleigh Hill, and before I knew it was jogging into Devil’s Dyke car park where my crew – driver Emily, pacers Mark and Chris – were waiting to greet me. I was, by this point, about an hour and a half behind ‘dream day pace’, but almost two hours ahead of 24-hour pace.

Getting to this point felt like a victory in and of itself. Ultras tend to lack the supportive atmosphere of big city marathons, so even a few words of encouragement from total strangers can lift your spirits. To have a team of three dedicated supporters giving up their weekend to help me achieve this lofty goal was nothing short of overwhelming.

I took a moment to change out of my sweaty T-shirt and swapped my sun hat for a trusty Ugoku cap. I felt like a superhero as my crew offered words of encouragement and support. Grabbing a few more gels and snacks from my food bags, I set off into the approaching night with my first pacer, Mark, feeling as though the finish was within my grasp.

I should have known, of course, that before the hero can complete his quest, he must first descend into hell.

Part three – Devil’s Dyke to Eastbourne

Heading off with Mark, I was immediately surprised by just how much having a pacer lifted my spirits. Mark is a gentle, easy-going guy (though tough, with a couple of hard-fought 50-milers under his belt), and the conversation flowed as we jogged the familiar descent off Devil’s Dyke and into the Saddlescombe aid station. I honestly felt as though I had about 10 kilometres in my legs, rather than over 100.

At Saddlescombe we grabbed a couple of freeze pops, which went down a treat, and quickly took off up the short climb out of the aid station before reaching Pyecombe Golf Club. This unremarkable place has always had a special place in my heart thanks to the starless night I spent wild camping on it during my 2018 South Downs Way through-hike.

Here the wind in my sails that picking up Mark had brought started to die down, and I had to start taking more regular walking breaks. It was around this time, too, that my feet started to play up. Whilst I’ve never had problems with blisters in the past, on reflection, the heat had meant I’d done a lot of sweating, which probably meant I’d been wearing damp socks all day. I had a spare pair in the car with Emily, but all day an ominous looking stain had been forming on my shoe around my left big toe, and I just didn’t want to have to look at whatever was going on under there.

Still, despite all this, I was able to keep it together enough to keep moving, and Mark and I enjoyed a few lovely moments taking in the spectacular golden hour views all around us. At around half nine, somewhere up on the ridge south of Westmeston, we donned our headtorches before powering and/or hobbling our way through the long rolling section of the trail heading into Housedean Farm. I managed to maintain a continuous run on the almost 2km-long descent just before the Bunkershill Plantation. At the time I felt like I was flying downhill, but checking my Strava file I was barely averaging 6:20 per kilometre!

By the time we got to Housedean, having picked our very steep descent down to the road, it was truly pitch black, and the race took on an altogether different quality. We were mostly running completely alone by this point, the field having spread out so that the only sign of other runners were bobbing headtorches in the distance. Sleep gnawed at the edge of everything, and on the long horseshoe climb out of the aid station Mark read out a message from my mum in the WhatsApp group: “Thinking of you as I go to sleep,” which was lovely to hear but made me realise just how tired I was.

Despite a small navigational error that saw us wandering into calf-deep grass and getting attacked by flies, we eventually reached the climb’s summit and took the sharp left-hand turn onto the ‘yellow brick road’, a roughly one mile-long, perfectly straight farm road that drops into Southease. Something about the repetitive downhill messed with my guts a bit, and I was quickly made aware of some unfinished business in the toilet department that needed fairly urgent attending to.

Thankfully, as mentioned, by this point we were relatively alone, and I was able to nip into a secluded hedgerow and, um, deal with it. (A note for any aspiring 100-mile runners out there: always carry a ‘shit kit’ – some toilet paper and a ziplock bag. It just might save your race.) We then resumed our descent, dropping down into South Farm and plodding our way along the track into Southease.

Despite having attended to the toilet situation, I was by now dealing with some uncomfortable chafing which I knew needed sorting out (I still had 30km left to run – a long way to go with red-raw… bits.) Luckily at Southease there was a very fancy toilet (with lights and everything), and I was able to clean myself up; heading out of the aid station I felt like a new man.

I don’t mean to dwell on it, but I cannot emphasise enough the importance of attending to stuff like this as soon as you can once it arises during a long race. Had I just ploughed on, rather than taking two or three minutes to sort myself out, I could potentially have been in agony for the final few hours of the race. Instead, I ran chafe-free and got to focus on the experience itself.

I expected the climb out of Southease to be one of the hardest stretches of the whole race for me. It’s just such a massive slog. Not all that steep for most of it, but with endless false summits and a lot of very gentle inclines which, by this point of the race, were for me more or less unrunnable. However, because I was so content with walking any climbs at this point, it ended up not being the sufferfest that it was during April’s 50-miler, when I was pushing the pace as much as I could.

After around an hour, we made it to Firle Beacon car park, where Emily was waiting for me with my second pacer, Chris. My best case scenario for getting to this crew point had been 11PM, and I got there at just after 1AM, comfortably ahead of the 2:45AM time needed to maintain 24-hour pace. Knowing I wouldn’t see Emily again until the finish line, I changed into a Watford FC T-shirt in memory of Dad.

I ummed and ahed about changing my socks, not wanting to reveal whatever state my toes were in, but in the end I decided to go for it. Peeling off the pair I’d run in for 19 hours, I was pleasantly surprised. The skin on my soles was, in places, pretty messed up, and there were a couple of blisters on each of my big and little toes. But there was no blood, and all my toenails were intact. I whipped on an almost-brand-new pair of Stance socks, and Chris and I got a move on.

Quite quickly, I was reminded why I had asked Chris to be my pacer for this final section, all the way back in September last year: first, he’s the kind of thick-skinned guy I’m comfortable telling to piss off if I have to; second, he’s a talker. So it was that we made our way along the never-ending ridgeline, Chris chatting away about all manner of things, me responding with yeses, nos, and grunts, eventually finding our way into the sleeping village of Alfriston, the penultimate aid station of the race, less than 10 miles from the finish.

Grabbing some more fuel from the aid station, my confidence was bolstered by the volunteers, who all said I was looking in pretty decent shape compared to many of the folks they’d seen ahead of me. I was able to put on a brave face, but by this point I was starting to really suffer, in ways that I had never experienced on a 50-miler.

I’ve heard people say that you’ve not really run an ultra until you’ve run 100 miles, and whilst I disagree as a matter of technicality, it was around this point in the race that I began to understand what it is that said people are getting at. It was as if the world around me was cloaked in a thick, soupy fog that slowed my attention and dulled my perception. I found myself unable to really think about anything, other than “This hurts.” My blunted awareness was counterbalanced rather acutely by sharp pains in my feet, particularly on the outer arch of each foot. At times, each step felt like I was sliding my feet over a fine cheese grater. “F*cking hell,” was just about all I could mutter under my breath with every downhill step.

Still, I knew that the back of the race was truly broken, with only two sharp climbs separating me from the finish line in Eastbourne. In 2021, when I first ran the SDW50, these climbs caught me off guard, and I found myself staggering up them in a state of disbelief that the race could dish out such a punishing section of trail so late in the day. This year, when I ran the 50 again in April, I was more prepared, and found them to not be so bad (perhaps because I was trying – and failing – to chase my buddy Jason up the first of them.)

At the 100, though, the climb out of Alfriston once again reared its monstrous head and left me scrambling around for a response. Chris was on hand to keep me distracted – as was an extraordinarily massive-looking Strawberry Moon – but I could’ve sworn the climb had doubled in both length and severity since Spring. At one point, a headtorch came wandering towards us from the darkness. We initially thought it was a runner who had perhaps gotten lost, or opted to head back down the hill, but it was actually just a guy out for a walk at 2AM.

Finally, the climb gave out, and once we got into Jevington, I allowed myself to really begin to accept that, not only was I going to finish this thing, but I was going to be very comfortably inside my original B-goal of 24-hours. Imbued with a newfound optimism, I grabbed a couple of fruit slices from the quiet aid station, and Chris and I jogged down the road towards the final climb. As we staggered up the slope, the early dawn light began to bleed over the horizon, and by the time the infamous trig point came into view (in, I could’ve sworn, a slightly different place than on the 50-miler…) the sky above Eastbourne was an inky blend of blues, purples and pinks.

We took a moment to commemorate having ticked off the last of the climbing. The volunteer stationed at the trig point directed our attention towards the town, where you could see the stadium housing the finish line, a view I’d never noticed on previous races. A glance at my watch indicated I’d been on the move for 21 hours and 30 minutes, which meant that sub-22 was, in theory, on the cards. However, I knew that between me and the two miles of flat road running through Eastbourne to the finish line there lay arguably the worst section of the entire course, at least insofar as my running skillset is concerned – a long, narrow, technical descent known affectionately as ‘the Gully of Doom’.

Even on a good day, I struggled to make my way down this trail at anything other than a careful, measured pace. I’m simply not a downhill runner by nature, and whilst I’ve made some improvements in opening up my stride and upping my turnover, technical descents are still my Achilles’ heel. With 95 miles in my legs, it was all I could do to stay upright – the overgrown vegetation intruding upon the trail, a result of months of cold, wet weather followed by the sudden arrival of summer, didn’t help. It just so happens that technical trails are pretty much Chris’s forte – he spent a lot of time on that trail waiting for me to catch up.

After much effing and blinding, though, we were clear of the trail and onto the final stretch of road. I was able to keep up a decent pace, in actual fact running my fastest kilometres of the whole race (and the only sub-6 minute kilometres all day.) Safely on the home stretch, I allowed myself to feel whatever it was that came up, thoughts of Dad flashing through my mind – but mostly I just felt insanely proud that I had pulled this off given the circumstances. Chris, meanwhile, nattered away about how zero drop shoes give him ankle issues.

As we cleared the cycle path and entered the athletics stadium, I glanced around to spot Emily and Mark, but couldn’t see them. Chris and I ploughed on, jogging merrily round the track – and just like that, it was done. Time on the clock: 22 hours, 12 minutes, 17 seconds. A volunteer congratulated me and handed me a belt buckle, ‘100 miles, one day’ emblazoned upon its rim. Success.

Aftermath and analysis

As it happened, Emily and Mark weren’t at the finish line. When they’d settled down for a quick nap in the Airbnb I’d booked for us in Eastbourne, the race tracker had displayed a predicted finish time about half an hour slower than I’d ended up running, which I think had something to do with it basing its predictions on my moving pace at that particular moment. They awoke to the panicked realisation that I was minutes away, and ended up arriving at the track just a few minutes after I crossed the line.

I was a bit of a hobbling mess for the first 24 hours after the race, partly due to exhausted legs but also due to the state of my feet. The next day (or, really, the same day), after dozing for a few hours at the Airbnb, we made our way back to London. Every step in my sandals felt like I was walking on razorblades. Getting down the stairs to our flat was a bit of an odyssey.

Thankfully, though, most of my discomfort was external. I’d been able to stay hydrated all day, even stopping to pee just a few miles from the finish line. And I’d had zero stomach issues, holding down gels, blocks, fruit, and crisps without any bloating. Of the 44 nutrition alerts my watch issued (one every 30 minutes for the duration of the race), I reckon I skipped maybe three of them, and only ever because I had just left, or was about to reach, an aid station with calories on offer. So the next day I had no particular internal discomfort, aside from a deep sense of fatigue.

In the week following the race, I opted not to run at all, and only did a couple of gentle short runs the following week. I’m now in my third week of recovery, and beginning to feel as though a more consistent running schedule is feasible. But I’m certainly not in a rush to build back any time soon.

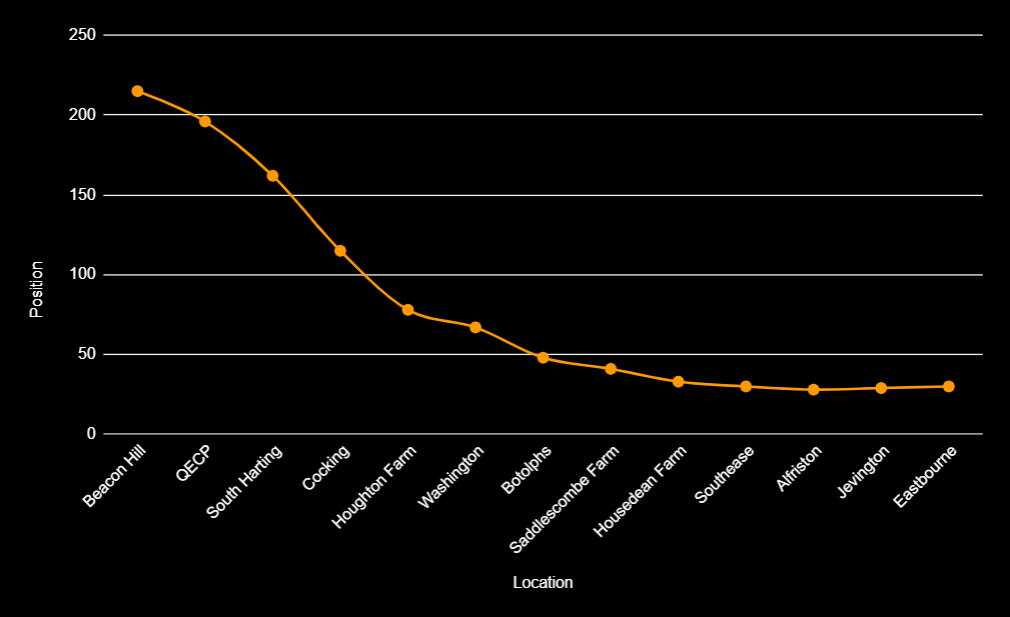

Looking back, if I compare my results with those of other runners, I fared pretty well. For a start, just finishing was an achievement – a whopping 45% of those who started the race dropped out, the highest ever DNF rate for the South Downs Way 100, and in the top ten for all Centurion events ever. The vast majority of these DNFs occurred during the day – those of us who made it to the night, it seems, did so by pacing it well. For example, when I got to the first aid station, I was in 215th place out of 340; by the time I crossed the finish line, I was 30th.

The fact that I finished inside the top 10% on my debut 100 I take to be a good sign. In a way, I feel as though I have found my distance. I’ve never been a ‘type A’ runner, and the kind of intense, close-to-the-fire suffering necessitated by ‘short’ distances (sub-50k, for instance) isn’t necessarily my preferred state. The strategy and problem-solving nature of longer events appeals to me, and I took this run to be a good sign that I might have some success over longer ultras in future.

Comparing my splits with those I had mapped out in advance, I ended up sitting somewhere in between ‘dream day’ and 24-hour pace. Which, given the circumstances, I am more than happy with.

I’ve since spoken to other finishers who confirmed the impact of the heat on their finish time. The fact that this year’s men’s winning time of 15:50 was more or less an hour slower than usual means I don’t think my initial goal of sub-20 was completely unreasonable. I certainly intend to do this race again, and when I do, I’ll have splits with which to compare my run. Having ticked ‘finishing a 100-miler’ off my list, a goal I might try and chip away at over the next few years is ‘finish inside the top 10 at a competitive ultra’.

For now, though, rest and recuperation, ahead of October’s Chester Marathon.

Oh, and one final note on fundraising – in the end, thanks to friends, family, colleagues, and complete strangers, I was able to smash my £1000 target and raise over £3000 for the Peace Hospice. And that achievement trumps just about any sodding race!