Western States Endurance Run

Posted by Ed on August 2, 2024

For posterity’s sake, I enjoy keeping a record of my races insofar as I can manage to. But in all honesty, so much of Western States exists in my memory as a series of images and sensations that I struggle to give voice to: loose rocks and rutted yellow dirt; hot air and cold water; Scott Jurek in a plastic crown.

Still, I’ve managed to walk through my experience as best I can. If you’re interested, read on.

Part of what makes Western States so special is the difficulty of securing an entry.

Thanks to the fact that a 4-mile stretch of trail early in the race passes through Granite Chief Wilderness, entries are limited to just 369 runners, the same number as took part in 1984 when the wilderness was designated a protected area. This limitation has resulted in a uniquely intimate atmosphere at Western States – ostensibly the biggest ultra in the Western Hemisphere, yet a race which is dwarfed by my local Parkrun here in Crystal Palace in terms of participant numbers most weeks.

In order to enter the race, runners have three options: finish in the top ten at the previous year’s Western States; secure a Golden Ticket via a number of sanctioned events around the world; or win a place in the lottery. For most mere mortals, myself included, the latter is the only viable option.

But simply entering the lottery is, itself, an arduous undertaking, requiring the completion of a qualifying event to secure a ticket. All such qualifiers are at least 100km long themselves, and most are longer than that. (Following a decision by the Western States organisers to stem the flow of entries, any event less than 100 miles is required to have an elevation gain of 2500m, eliminating many ‘entry-level’ 100ks from consideration.)

Once you’ve gone through all the highs and lows necessitated by the completion of a qualifier, you’ll be granted one ticket in the Western States lottery. In other words, one ticket in a lottery of around 10,000, competing for roughly 250 publicly available places.

Suffice it to say, one ticket is unlikely to be enough.

To ensure fairness, then, Western States will double your tickets for each year you do not get in, so long as you continue to run a qualifying race each year. This is a clever invention on the part of the organisers to ensure people do not simply give up on the idea of ever running the race themselves – it is not uncommon to hear of people with 128 or even 256 tickets in the lottery, having qualified and entered 8 years in a row. Other race organisers would do well to copy this system (I’m looking at you, London Marathon.)

The brilliance of this system is the way in which it genuinely ensures your chances of securing an entry increase year on year, whilst preserving a degree of randomness in the selection process which contributes to a mixed pool of runners making it to the start line. Seasoned veterans for the most part, but with a few lucky amateurs thrown in for good measure.

I was one of the lucky latter – a ‘one ticket wonder’. I ran my first and only qualifier at the South Downs Way 100, entered a single ticket, and my name got called in the lottery. I wasn’t even watching the livestream.

It’s not that I didn’t think I’d get in – I didn’t even think to think that I wouldn’t get in. It simply wasn’t on my radar. I was watching TV, and my phone was in the other room. When I eventually picked it up I was met with a flurry of messages from friends and well wishers asking, “Were you the ‘Ed Scott’ they just named?!”

Well, reader, I was and am that Ed Scott. And this is my Western States story. Lottery aside, it isn’t a particularly notable one – I didn’t finish in a remarkable time, or have any astonishing mishaps or epic lows to navigate. But it’s a story I am proud of, and one I will happily tell to anyone who asks about it for a long time to come.

So brew yourself a cup of tea and put your feet up, because we’re going to cover each and every step of this journey, starting back in December 2023 when my lucky stars first aligned.

Training

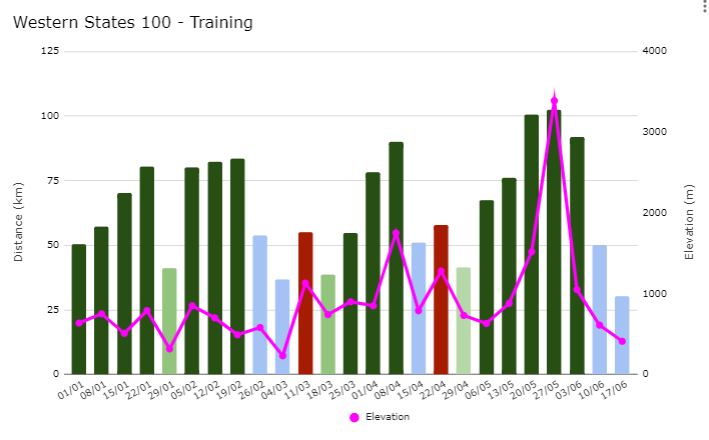

Pretty much as soon as I got in (once I had scraped myself off the ceiling) I started training. I had spent the prior couple of months ticking by on relatively low mileage following successfully pulling off my first sub-3 hour marathon in October at Chester. My plans for 2024 had not yet solidified, but I remember being pretty sure I didn’t want to take on another 100-miler after South Downs Way. Funny how that worked out.

Within a few weeks things started to fall into place in terms of how to build over the subsequent 26 or so weeks. With that much time to prepare, I knew a major risk would be overpreparing or doing too much too soon. Booking in a couple of B-races helped provide some ‘tent pegs’ in the otherwise unstructured time that lay between me and Western States.

The first of these was the Moyleman, a hilly trail marathon in Lewes, East Sussex, eleven weeks into my training. I broke this down into three chunks – a four week build from my base mileage of 50km to around 80km a week, followed by a rest week; then another three weeks floating at 80km a week; and then finally a three week taper.

Those numbers might not sound like much to some, but in that eleven week base build I actually think I trained better than I did throughout the training block for my first 100-miler at South Downs Way.

Whilst there was never a ‘typical’ week, the structure I broadly aimed to maintain each week looked something like the following:

- Monday: Track workout or hill session

- Tuesday: Easy run commute

- Wednesday: Easy run and gym session

- Thursday: Easy run commute

- Friday: Rest day

- Saturday: Long run

- Sunday: Easy run

Lots of slow-but-steady run commuting made a real difference to my fitness, and towards the end of this block I found myself able to trot gently up steep hills with a with a heavy backpack and keep my heart rate below aerobic threshold. I felt in great shape by the time I toed the line at the Moyleman which, hills and trails aside, couldn’t have been more different than Western States. It was cold, wet, and extremely sloppy underfoot from gun to tape. But I was pleased to walk away with 5th place in 3:38 at a reasonably competitive event.

My next warm-up race was the Chiltern Ridge 50k, which came just six weeks after the Moyleman. I focused on recovering as quicky as possible with a rest week before building the course of three weeks. My weekly structure didn’t vary all that much, though I stopped going to the gym as I upped the mileage.

The big difference with this short block was that I focused considerably more on elevation gain by getting my weekend long runs in out in the North or South Downs. Strava indicates I ran 90km and climbed 1750m in my final build week of this block. I then experimented with a short, two-week taper before Chiltern Ridge, which seemed to work quite well – I ended up taking third place at that event and breaking my 50k PB by a couple of minutes despite that PB having been set on a pancake-flat course.

By this point in my training, I felt I had done enough to feel confident about my fitness and endurance. But there were two missing pieces of the Western States puzzle to work on – time on feet, and heat training. With regards to the former, I tend to err on the side of caution when it comes to long runs, and generally subscribe to the philosophy that going beyond three hours too often is likely to do more harm than good, especially early in a training block. But I knew that it would be important to get some long days in not so much for the fitness payoff but for the chance to practice my nutrition, try out different kit and clothing, and generally undertake some ‘dress rehearsals’ for what it is like to run 100 miles.

Heat was less straightforward. Following a bleak winter, there were no signs of the May heatwave I had been hoping for, the likes of which we have seen in the UK in recent years. As I built up my mileage and the final peak weeks of my training drew nearer, I decided to bite the bullet and book myself a ticket to Mallorca for a solo training camp of sorts. Four weeks out from Western States, I headed to Port de Sóller on the rugged north coast of the island. Over the course of three days, I ran about 80km and climbed 3100m, all on very technical Mallorcan trails. So technical, in fact, that a 43km run ended up taking me about 8 hours as for so much of it I was reduced to a walk or, at one point, a buttslide.

Without realising it, I ended up running a large chunk of the new UTMB Mallorca course, including the frankly bonkers Na Martorella climb which, I have to be honest, felt unsafe to send a few hundred runners up in an organised event. Time will tell how that plays out.

Whilst these Mallorca runs were not hugely beneficial aerobically due to the aforementioned walking and buttsliding, they were a massive confidence-booster in terms of preparing for Western States. I spent hours out in the heat of the day, managing my nutrition and hydration excellently and remaining calm when confronted by unexpected challenges (such as taps that, despite being indicated on a map, did not exist or did not work.) Psychologically, you couldn’t ask for better 100-miler prep.

After Mallorca, in the final weeks leading up to the race, I booked a couple of sauna sessions at a local spa. Spending time sat in 80°C is supposedly sufficient to engender the kind of physiological adaptations necessary to cope with hot weather racing. The benefits allegedly only last a couple of weeks, so it wasn’t something I worried about too much until closer to the race.

The result was that, by the time I hit my taper, I felt about as fine as you should expect to feel at the end of a long training block – which I would chalk up as a win. I was injury-free, fitter than I’d ever been, and felt like I had done everything I could to prepare for Western States. All that I had to do now was get out to California.

Pre-Race

I flew out to America with my girlfriend Emily and my mum 10 days before the race. We had planned a trip taking in San Francisco, Yosemite National Park, and Lake Tahoe before the race, and Monterey Bay afterwards. I had spent quite a bit of time in the USA a few years back, but the closest I’d come to Northern California was Eugene, Oregon (and, weirdly, Palm Springs.) Say what you will about the country and its politics, but I absolutely love spending time in the USA, and this trip was no different.

This isn’t a holiday report, so I will spare you the postcard. But I will say that Yosemite National Park was the perfect place to visit the week before the race. Whilst I only did a handful of runs on the entire trip, the moderate hikes we completed in Yosemite were the perfect way to acclimatise – the weather was pushing 30°C, and we flirted with an altitude of 2500m (8500ft) upon summiting Sentinel Dome. Not exceptionally high, but high enough for this lowlander to feel the impact and get a sense of what the first third of Western States might feel like.

Before I knew it, we had checked into our hotel in Truckee, a short drive from Palisades Tahoe. On the Thursday before race day, we headed over to the resort to check out some of the pre-race hullabaloo. It was quite surreal seeing folks like Dylan Bowman, Billy Yang, and Sally McRae just wondering around the place. We took front row seats for some pre-race panels with folks like Hayden Hawks and Leah Yingling, and headed up the first half a mile or so of the infamous escarpment climb. But I knew from listening to AJW’s chat with Jason Koop on the latter’s podcast that I shouldn’t spend too much time hanging around tiring myself out, so we soon headed back to the hotel.

That evening we met with my pacers for dinner on the north shore of Lake Tahoe. Bowdy and his daughter Sierra and I had connected via the Western States pacer portal some months back. After a couple of Zoom calls, we agreed upon a strategy – Sierra would pace me down Cal Street, from the 100k mark at Foresthill to the infamous American River crossing. There, Bowdy would pick me up and run me to the finish line in Auburn. We also decided last minute that they would meet me at Dusty Corners, mile 38, rather than Robinson Flat at the 30-mile/50k mark.

It is worth mentioning that Bowdy and his wife Bonnie flew out from Michigan to be a part of my race, whilst Sierra drove up from the Bay Area. Such is the esteemed nature of Western States that people will travel from across the country just to help a total newbie like me. I was and am immensely grateful for their support and hope to repay it at a European event some day.

The Friday before race day is the expo proper, where runners register for the race and collect their bibs and stash. The ‘goody bag’ at Western States is a literal backpack of stuff – sunglasses, recovery slides, socks, you name it. The only thing I was slightly disappointed not to receive was any sort of race T-shirt. I ended up buying a Hoka T-shirt and getting it printed with Western States 2024 along the bottom, but it would have been nice to have a T-shirt with the Western States logo that I could wear out and about and pretend that people I pass in the street give a shit.

When you think about the fact that, in terms of participants actually on the course, Western States is about the same size as my local Parkrun, it’s quite remarkable just how much of a buzz there was in and around the expo. Brands just showed up, ostensibly to support their elite athletes but also probably just to capitalies upon the craziness. Nike Trail, for instance, who are not affiliated with the event, gave every runner a free pair of shoes just because they were there. (Unfortunately they ran out of my size – despite taking my email and promising me they’d send me a pair, they never got in touch.) Hoka, the title sponsors, were selling 100 pairs of their limited edition Tecton X 2.5, the shoe Jim Walmsley wore to win UTMB. (At $300 a pop I gave it a pass.) Squirrels Nut Butter were dishing out temporary tattoos – I watched one guy get a squirrel emblazoned upon his buttcheek.

Suffice it to say, the atmosphere was very different to, say, the South Downs Way 100. At one point, after deducing my free Hoka slides were a size too big, I headed back to registration to see if I could change them. As I waited for one of the countless volunteers to swap them out, who should rock up to register at the last possible minute but the GOAT himself, Jim Walmsley. I played it cool, of course – he didn’t look like he was keen to dish out selfies – but I did wonder if he spotted me and thought, “Isn’t that the guy who came third at the Chiltern Ridge 50k?”

After catching the pre-race elite athlete spotlights – during which I spotted Gordy Ainsleigh dishing out massages in the middle of the crowd, complete with a full massage table – we dropped off my kit bag with my crew and headed back to the hotel via a pizza dinner to rest and prepare. I laid out my race kit, walked myself through the crew plan one last time, and then headed to bed around 7pm.

The Race

I awoke to my 2:30am alarm feeling surprisingly rested and calm. I went through my standard pre-race rituals – sipping on some strong black coffee, applying liberal vaseline where it’s needed, and popping in my contact lenses. I had deliberately avoided wearing any of my race day clothing all holiday, partly out of nervousness around laundry access, but also in a bid to ensure those clothes retained their symbolic power. There is something to be said for donning a uniform when you’ve got a job to do.

We headed to Palisades Tahoe for around 3:30am. A group of supporters and volunteers were heading up the escarpment when we arrived, and I got chatting to one of them whose name I sadly didn’t catch but who clocked my bib number (300) and said he’d see me at Cal 3 aid station.

The pre-race breakfast for runners was already laid out – I had taken a risk in relying on this rather than sorting anything in the hotel, but I the 5am start meant I didn’t have much of an appetite anyway. I settled for a blueberry muffin and another cup of coffee. It went down fine.

Slowly the resort filled up with runners and crews, and the anticipation began to build. Dawn began to show itself, though the valley floor was still in darkness, and quite cold. Some other runners were wearing quite a lot of layers, but I wore just a T-shirt in anticipation of the 4-mile uphill hike that awaited us. There was just enough time for one last toilet visit, which was regrettably unsuccessful. But I felt empty enough to not be worried.

Before I knew it, we were being called to the start line. I said goodbye to mum and Emily and headed over. There, I bumped into fellow Brit James Poole, another of the three London athletes in the race and the only other runner I knew from ‘real life’. We wished each other luck and grabbed a quick selfie, and then the countdown started, and then a shotgun went off and we were running Western States.

The Escarpment to Robinson Flat

Mile 0 – 30

On the aforementioned pocast with Jason Koop, AJW highlighted five ‘pinch points’ where runners can easily lose control of the race and ultimately scupper their chances of success. The first of these comes right out of the gate. Western States famously starts with a 750m climb up what’s known as ‘the escarpment’, into the high country that defines the start of the race.

This climb is liable to do damage. Months of training and anticipation all leading up to this moment mean many runners simply take it too fast, and I was keen to avoid that mistake.

Immediately upon crossing the start line, we were met with a wall of noise. Spectators lined each side of the trail and for a couple of hundred metres all I could see and hear was people cheering – no, screaming. The atmosphere was electric and unlike any I’d experienced at an ultra. I knew, though, to keep my cool.

I settled into a steady power hike and focused on just taking it all in. I chatted with fellow runners, including a lady from Kentucky, and even bumped into one of the handful of other Brits taking on this race. Will had qualified via Race to the Stones (before they changed the rules around what constitutes a qualifying 100k) and was taking on his first 100-miler.

I don’t know if it was the altitude, my nerves, or perhaps a bit of both, but my heart rate on this climb, despite my steady, controlled effort, kept wobbling around my aerobic threshold. This was concerning, as I had hoped to keep it well under 140 for the first part of the race. But I did my best to keep it in check and otherwise not let it panic me.

After a few miles, the sound of cheering returned, and as we climbed a particularly steep, rutted out section of singletrack, spectators once again began to appear on either side of the trail. Their words of encouragement were not just sincere – they were forthright, passionate, and urgent. Nothing like a UK race, where the best you can hope for is a quiet ‘golf clap’ and a polite, “Well done.” Here, nearing the highest point of the race at 8600 feet, the trail became a tunnel of cheering spectators, ringing cow bells and screaming at the top of their lungs. At one point, a man thrust an entire box of Krispy Kremes in my face and yelled, “DONUTS!”

Finally we reached the very top, and I made a point of looking back down over Olympic Valley before descending. The dawn light cast everything in a soft, amber glow. It was beautiful – but I had a race to run.

Dropping off the other side of the mountain, the trail that follows the escarpment is one of Western States’ great secrets. Film crews documenting the race rarely cover this remote part of the course, and most documentaries on past champions cut from the escarpment summit to Robinson Flat, leaving out 30 miles of some of the race’s most stunning terrain. I had very little idea of what to expect, other than the fact that it would be slow-going.

As it happens, the trail is actually quite runnable for most of its course. It winds around the side of the mountain through wildflower meadows and pine forests. Underfoot, there are a number of water crossings, and a few sections where the trail itself is literally a stream. (The Western States Foundation are currently funding a new trail a hundred feet higher up the mountain which will apparently be less prone to flooding.) There are some steep descents here and there, too.

I spent much of this section doing my best to sit back and relax. There was some jostling for position as people traded places on the narrow single-track trail, but mostly people settled into a conga line rhythm, content just to be where they were. We were extremely lucky that there was almost no snow at all on the ground – I think we crossed maybe two or three short patches in total all day. The previous year, almost the first 20 miles had been on snow and ice.

At one point, as we began to descend a long series of switchbacks, I heard another British accent up ahead. I soon caught up, and said hello to Nadine, the third Londoner at Western States. Nadine had come out weeks earlier and recced the entire course, and as a result she was looking strong and moving so well. It was great to share a few miles with her and chat about the crazy journey we were on.

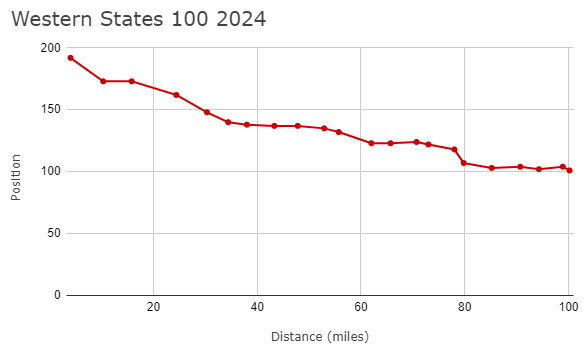

Before long, we hit the first aid station at Lyon Ridge, around 17km in. I noticed that I was, already, 23 minutes behind what Western States advertise as 24-hour pace, but I tried not to dwell on this. In all of my ultras, I have started conservatively and moved gradually through the field, so I knew that I might be a statistical outlier with regards to the dataset Western States were using to calculate a ‘typical’ 24-hour runner’s splits. The important thing was that I was feeling strong and comfortable.

I knew not to dawdle, so I drank plenty of water, refilled my bottles, grabbed some fruit and walked out before I had time to overthink things.

As the trail slowly wound its way down through the high country, the trail became wider, dustier, and rockier. I did my best to keep up a steady pace, though my heart rate was still a bit of an issue, spiking close to my aerobic threshold every time I picked up the pace, even on the downhill. I was also having some gastrointestinal issues – nothing major, just a slight stomach ache, which I concluded were probably a result of the altitude and the early start and resulting complications around breakfast and toilet timings. Not wanting to make any silly mistakes, I removed the Naked Running Band I was wearing around my waist, and felt some relief with regards to my stomach.

Despite still taking it very conservatively, I now know that I overtook 19 people from the top of the escarpment – where I was 192nd – to Lyon Ridge – where I was 173rd. Between Lyon Ridge and the next aid station at Red Star Ridge, however, I passed, and was passed by, a net zero amount of runners. This section of about 5.5 miles took me an hour and fifteen minutes, which should give you some indication of the kind of terrain and elevation involved.

On the descent into Red Star Ridge I kicked up quite a bit of dust and felt it fill my shoes. I made a point of sitting down and taking my shoes off at the aid station to clear it out. Again, I drank a lot of water here and helped myself to some watermelon. On the way out I caught site of a photographer and tried to strike a pose with my slice of watermelon, but then I realised he was just there to photograph a friend and felt a bit stupid.

Over the course of the next few miles I found myself yo-yoing with a Japanese runner – she would fly past me on the descents, but then I would catch her on any uphills. Leapfrogging like this, we soon caught up to a pack of around 10 guys, and I let myself sit on their heels as the conga line wound its way along the trail. Slowly but surely, I ended up overtaking around half of them, and ended up with a breakaway pack. Again, without really trying, I overtook more runners, and before I knew it I was leading the pack through the high country. It felt great, this silent cohesion and unspoken teamwork keeping us all going.

The section from Red Star Ridge to Duncan Canyon aid station is the first net-downhill part of Western States, descending 500+m in just over 13km. I made the mistake of thinking this section would therefore breeze by, but in actuality it’s still a tough run, with over 250m of climbing along the way. Most of the descending actually comes right at the end, when the trail drops about 300m over the course of 4km into the aid station. I ran this descent well, though, and got to Duncan Canyon at around the 24.5-mile mark in 5:26 overall. A quarter of the race done, though closer to a third of the climbing.

It’s here I have to take a moment to highlight just how incredible the volunteers are at Western States. This was the case at every aid station, but for whatever reason at Duncan Canyon they were impeccable. As I arrived at the aid station – my bib number having been called in advance to give the volunteers fair warning – a guy whose name I regrettably don’t recall greeted me and asked if I wanted anything. I assumed that when I said, “Water and electrolytes,” he would simply point me in the direction of where I could get those things. Instead, he became my chaperone, taking my bottles, filling them up, and continuing to ask if there was anything he could do to help. It was almost a little overwhelming, but I knew to embrace it as part of the experience.

As I nibbled on fruit from the aid station the Japanese runner with whom I had been yo-yoing came in. I gave her two big thumbs up and told her how strong she was looking. I don’t think she spoke much English, but she smiled and said thank you. One of the aid station volunteers leant in to her friend and said, “It’s great to hear so many different accents today!” We chatted briefly, and as I explained that I was one of a handful of Londoners in the race, her friend revealed that she was in fact from Bolton, Lincolnshire. “What brought you over here?” I asked in surprise. She simply gestured to the vast mountain wilderness surrounding us and smiled. “Ah,” I said, “I see.”

Before leaving Duncan Canyon I asked if they had a toilet as I was still experiencing some GI issues. “Number one or number two?” my chaperone asked me. Before I said anything, he said, “Either way, you’ll need to find a bush – there’s no toilet until Robinson Flat.” I gave it some thought and decided to press on – my stomach had calmed down a bit anyway, and Robinson Flat was only 9.5km away. But not before dunking my hat and buff in an ice bucket in anticipation of what was awaiting me over the course of the next 90 minutes – the second ‘pinch point’ mentioned in AJW’s podcast: Duncan Canyon.

Just looking at the numbers for the split between Duncan Canyon aid station and Robinson Flat, you can see why it’s so tough: 9.5km, ~100m of descending, ~500m of climbing. That’s a lot of climbing. However, the descent into the canyon is really easy going. It’s the first part of the trail that doesn’t feel like mountainous high country but actually the kind of trail you might be able to reach on a regular training run. The steep canyon looms to your left-hand side, though, reminding you of the monstrous climb that awaits.

By the time I reached the bottom, it was gone 11AM, and the heat of the day was starting to kick in. I waded through Duncan Creek, dipping my hat and buffs once more in the ice cold water, and began the climb. At first, I remember thinking to myself, “This isn’t so bad,” but that’s because I was thinking about the climb like it was a southeast England climb, that would maybe take 20 minutes tops. 500m is just a really bloody long way, and with the heat of the day and the fatigue from having already covered close to a marathon, it was the first part of the race where I properly suffered.

The climb ended up taking me just over an hour. On the race map and on my Strava file, it’s a blip – a 6km section that blurs into the vastness of a 160km race. I don’t even remember much about the hour that I spent on it. But I know it sucked. The trail was burnt out from a forest fire some years ago – it was hot and exposed, dusty and dry. Quintessential cowboy terrain. The only silver lining is that I had known it was coming. Sometimes (often) ultras are just about toughing out the shitty bits and then recovering. The challenge is remembering, in those tough moments, that this bit won’t last forever and that you can and will recover once you get through it.

And guess what? I got through it. I reached Robinson Flat, and found myself running once again. Crews and spectators lined the fire road, sat out in deck chairs beneath parasols in the heat of the day. They whooped and cheered as I passed and I did my best to look thankful as I closed in on the 50km mark and the end of the high country terrain which defines the first part of the course.

At Robinson, I finally got to make use of a toilet, which was a blessed relief. An aid station volunteer equipped with a hose sprayed me down with ice-cold water, and two more filled a pocket on the back of my pack with ice. As I jogged out of the aid station the ice was bouncing all around my shoulders and falling onto the floor. It felt completely bizarre, but it made a real difference to have cold water trickling down my back. Before I knew it, I crested the short climb out of Robinson Flat and began the half marathon descent into the infamous ‘canyons’ section of the course.

Robinson Flat to Foresthill

Mile 30 – 62

The prospect of a 13-mile net downhill section had sounded appealing on paper, but the reality of it was quite different. With 50 mountainous kilometres already in my legs and the heat of the day beginning to make itself felt, finding a comfortable running rhythm (and staying in it) was quite a challenge. Especially because my heart rate was continuing to cause issues – even at a gentle jog it was sitting right at my aerobic limit.

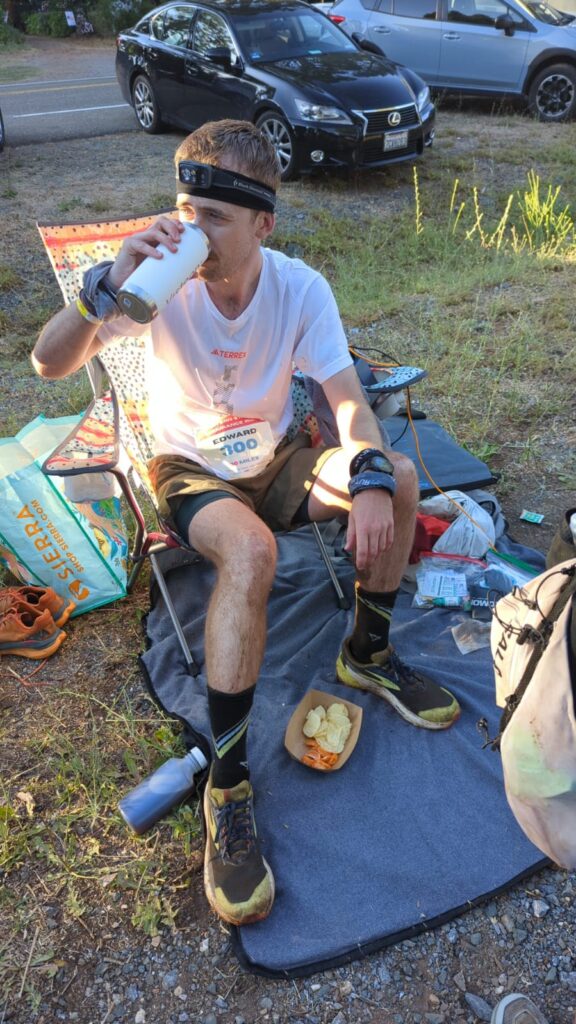

Despite this, I was able to maintain a decent pace. I more or less breezed right through the Miller’s Defeat aid station, stopping just to refill my bottles and douse myself in cold water again. I fell into a rhythm with a pack of guys, including a South African runner who had qualified via UTCT and a guy from Idaho. Initially I thought this pack were moving too quick for me, but I was pleasantly surprised to find myself sitting comfortably on their heels as we jogged our way into Dusty Corners, where I was scheduled to meet Bowdy, Bonnie and Sierra for the first time.

At Dusty, Bowdy greeted me as I left the trail and put my plan into action. He had a bottle of Coke ready to go, and whilst I drank that and walked through the aid station he filled up my other bottles. When I got to the crew area, Sierra and Bonnie had set up a chair for me. Despite the mantra “Beware the chair” ringing in my ears I made use of it, changing out my socks as per my plan and drinking as much water as I could. It was great to hear words of reassurance from the three of them that, despite my concerns around being behind pace, I was well on track for a 24-hour finish according to Bowdy’s calculations.

Before I knew it, it was time to set off again, and with a pack (and hat) full of ice I made my way down the fire road and out of Dusty Corners. The trail quickly veers off to the right, where it hugs the canyon wall for a few miles of beautifully runnable single track. I found myself really flowing through this section, my spirits revitalised by the encouragement and interaction with my crew. It’s amazing what a difference a few minutes of TLC can make – where I had felt as though a slow shuffle was all I could muster on the way into Dusty, on the way out I was able to run with a long, clean stride. Maybe the caffeine in the Coke helped too.

50 minutes later, I reached Last Chance, signifying the end of the downhill half marathon section and the start of the canyons proper. As I went through the motions of what had become, at this point, my aid station ritual – water, Coke, ice, sponge showers, etc. – I chatted to an aid station volunteer and asked just how bad the approaching Devil’s Thumb climb was. “I’m not gonna lie,” she said, “it sucks.”

After a long descent into the canyon via a seemingly endless series of switchbacks (I counted 25 before I gave up), I crossed the famous Swinging Bridge – where a couple of hikers had set up a hammock and were bathing serenely in the heat of the canyon – and began the climb up to Devil’s Thumb. I soon found out the aid station volunteer was not lying: the only way you can squeeze 500m of climbing into 3km of trail is by making that trail very, very steep and ugly. According to Strava it took me 45 minutes to reach the top. It was not pleasant.

But – despite the climb being absolutely horrendous and me being reduced to a quivering wreck by the time I reached the top, I was able to maintain enough mental composure to notice that I was consistently passing people on the way up. I think I overtook 5 or 6 people in total. Where others were taking slow, steady steps, I was able to keep up a decent power hike and keep my heart rate aerobic the whole way up. So I took some solace in knowing that, despite how terrible I felt, I was ostensibly moving better than others.

When I finally reached the top, a small boy was singing at the top of his lungs in encouragement. He called out my bib number into a walkie talkie, and I took a moment to look to my left at the Devil’s Thumb rock formation which lends its name to the climb before jogging into the aid station. I was really shaken up by the climb, to the extent that I couldn’t really imagine having to traverse a further two canyons before I got to see my crew again. But the aid station volunteers were once again fantastic at looking after me, and after some more Coke, ice, water, and a very welcome popsicle, I began shuffling my way along the trail towards the second canyon, El Dorado.

The descent into El Dorado was considerably harder than Deadwood. For a start, it is eight kilometres long. Eight kilometres! Downhill! With an average gradient of -10% and probably close to 200,000 switchbacks. That’s a big effort on any day, let alone after having just ticked off Devil’s Thumb. Plus, the terrain underfoot was considerably more technical than the buffed out trail into Deadwood. I remember swearing to myself quite a lot in this section and almost tripping over a couple of times. But all in all I seemed to be holding it together better than the couple of people I passed. Somewhere on the descent I passed the halfway point of the race in 11:25 or thereabouts, giving me a relatively narrow – but still achievable – margin in which to secure a sub-24 hour finish.

At the aid station, which this time was at the bottom of the canyon, I took a moment to sit down and take my shoes off, shaking out the dust that had accumulated on the descent. The volunteers at El Dorado are all Western States legends – I believe Tim Twietmeyer filled my water bottles – but honestly by this point I was too fried to say them much beyond asking them how the hell they got all their supplies down into the canyon. One guy laughed and said it had taken them five days.

The climb from El Dorado to Michigan Bluff is just under 5km but it took me almost an hour thanks to the 500m of elevation gain it encompasses. I don’t remember much about this section other than spending quite a bit of time thinking about the forthcoming Volcano Canyon section, which AJW had flagged as the third pinch point on the course. I got into Michigan Bluff where I spotted Yassine Diboun on a megaphone and none other than Gordy Ainsleigh again. I knew that my crew were at this point less than 10km away, so I did my best not to linger, sticking to my routine of fruit, water, and ice. By this point the evening was starting to cool a little and ice was starting to feel obsolete, but it was still refreshing nonetheless.

Trudging out of Michigan Bluff on the fire road I leapfrogged here and there with a couple of runners. It was very clear that some had paced themselves very well through the early, tougher portions of the course and were still moving strong, whilst others were already grinding to a slow shuffle and staring down the barrel of a 70km walk to the finish. I was passing most people and still able to run gently uphill, which I took as a good sign that 24 hours was still on the cards.

Nearing the top of the fire road ascent, I noticed a series of pink ribbons – the same kind used to mark the Western States course – strung to a fence on my right hand side. At first I suspected foul play, but when I looked down the hillside the ribbons continued for at least 200m off into the brush. I knew that the course left the fire road at some point, so despite my better judgement I opted to follow the ribbons rather than carry on around the corner.

This was my first real mistake all day – the ribbons were in fact a red herring. I can only assume someone had deliberately moved them, and that someone was hell-bent on ruining people’s day, because the ribbons went right off into the distance. But there was no trail underfoot, just increasingly dense bushes, scrub, and an ancient barbed wire fence. After a minute or two I realised my mistake and scrambled back up the hillside in a bit of a panic.

All in all, I maybe lost three minutes to this mistake, but it’s hard not to let things like that play on your mind. What if those three minutes were the difference between a silver and a bronze buckle? I dared not entertain the thought. I did my best to put it behind me and not overcompensate by running too fast. Soon, I was catching the same people I had passed on the way out of Michigan Bluff. I made a mental note to try and reduce my planned 10-minute crew stop to make up for the lost time, if it felt sustainable to do so.

A few minutes later, I made my second mistake of the day. For some reason I had clearly not fastened one of my water bottles properly at Michigan Bluff, and when I went to drink from it, the lid came off and electrolyte mix began pouring all over me. By the time I’d scrambled to put it back on I had maybe 200ml left. With maybe 300ml of pure water left in my other bottle, it was less than ideal. But again, you can’t expend too much energy getting frustrated over these things. If I ran out, I would just have to rehydrate at Foresthill.

The Volcano Canyon descent eventually arrived, and in all honesty it wasn’t as bad as I had worried. It was certainly steep and ugly, but at around half the length of the previous two canyons, and with the Foresthill mark so tantalisingly close, it was just a matter of shutting up and getting myself up it. I caught back up with the Idaho runner I’d run with into Dusty Corners, and we got chatting about some of the mountainous ultras he’d done in his home state. By comparison, my tales of the South Downs Way 100 felt a bit tame.

Eventually the trail underfoot gave way to tarmac road into Foresthill, though the climbing barely relented. I noticed I was holding back on drinking water due to my dwindling supplies, and made a conscious effort to down most of my remaining water, knowing that Bowdy would likely be around the corner with more water soon. I picked my feet up and did my best to run as much of the hill as I could, and sure enough as we rounded a corner Bowdy was there with a bottle of Coke in hand. I tried to explain the frustrations of the last section, but even as I was telling him I knew it was water under the bridge – what was he going to do about it, anyway?

The climb finally relented and we hit the road into Foresthill. This was the first time all day I’d had a pacer by my side, and it honestly felt great. The crowds began to pick up and before I knew it we were right in the heart of it. It felt like quite a shock to be back in civilisation in comparison to the 100+ kilometres of almost complete isolation that had come before. A bit like that feeling when you’ve been up on a mountain and you finally make it back to a ‘normal’ altitude. Everything felt familiar, safer, nicer.

Sierra met us at the aid station and set to work refilling my bottles whilst I headed over to the crew area with Bowdy and Bonnie and sat down. I had pencilled in a potential shoe change here, but my Brooks Catamount 2s were presenting me with zero issues, so I opted to stick with them. I did however change into a fresh T-shirt, switch out my hat for a headband, don a headtorch, and drink as much water as I could manage to compensate for the previous dry spell. Six minutes later I was ready to go. I must have been quite efficient in the aid station as I apparently overtook nine people between the timing mats at Michigan Bluff and Foresthill.

Sierra and I headed off down the road. All that remained were 60 relatively runnable kilometres. Easy.

Right?

Ha!

Part Three

Foresthill to Auburn

Sierra and I set off down the 11-mile section known as the California/Cal Street trail. Sierra sat in front for most of this, and did exactly what I wanted – talked about anything and everything. I did my best to ask her questions about her PhD, her racing experience (she had run one of the Canyons by UTMB events on this very stretch of trail), her upcoming debut 100-miler in Oregon. But mostly I just listened, grunting affirmations where I could and doing my best to sit her on her heels.

One thing I will say about Cal Street is it is not flat. Everybody talks about Western States as if it’s all downhill from Foresthill, and that is just not the case. Yes, the trail itself is smooth and runnable compared to much of what has come before, but there are multiple rollers along it, some of which kick up a real fuss – my Strava reports a couple of 25+% gradients here and there on this section.

As we made our way along the trail, the sun began to set and we flicked on our headtorches. My pace was notably slowing but I was still able to maintain a run on the flats and downhills, and a solid power-hike on the ups. Somewhere between Foresthill and Cal-2, we spotted a familiar figure on the trail ahead. I did my best to muster up a bit of enthusiasm as we passed the legendary Sally McRae, who was sadly having a rough day out there. She was genuinely so lovely and cheered for us as we passed her and her pacer. I almost felt like apologising, like I was defacing sacred ground.

At each of the aid stations along Cal Street Sierra was a consummate professional. At the first I was still relatively coherent about what I wanted and needed – chicken soup was on offer, which went down very well – but as we progressed I was less and less able to think clearly. Despite this (and despite not knowing me at all), she took care of everything, taking my bottles off me and refilling them, making sure I got some food in and drank some Coke. I knew as we progressed down the trail that I had made the right choice in electing to find a pacer – I simply wouldn’t have made anywhere near as good a time in this section without Sierra’s guidance and support.

The fourth pinch point AJW mentioned on the podcast I listened to was the section of trail between Cal-3 and the river crossing. The problem with this bit is that you can more or less hear the river – at times you can smell it and feel the cool air coming off it – but you still have four miles to go until you cross it. Four miles with the same short, sharp rollers you’ve been dealing with for the previous few hours. I tried not to let my mind run away from me as we trotted our way along the trail, but on a few occasions I remember muttering, out loud, “Where is this bloody river?!”

Eventually, we heard the tantalising buzz of human activity, and as we rounded a corner the floodlit river crossing yawned into view. By this point I was struggling to really communicate, but I did my best to thank Sierra as she passed over the gauntlet to Bowdy and we made our way into the river.

The river crossing itself was borderline psychedelic. All the videos I’ve ever watched of it have been of elites, who tend to reach it late in the afternoon, during the hottest part of the day, where it offers welcome relief. Crossing it at night was something else.

The only way I can describe it is by asking you to imagine crossing an ice-cold, fast-flowing river in the middle of the night when you’ve already run 125km, and now imagine the river is full of glowsticks illuminating the craggy rocks and there are people in the river in wetsuits telling you to keep going, and now imagine the river is up to your chest and the rope you’re holding onto keeps swinging because other people are using it as well and your feet keep sliding on the rocks and all your chafes and blisters are lighting up like they’re on fire in the cold water and your headtorch is illuminating your feet at the bottom of the river. That’s what it was like. I kept saying, “What the fuck,” but quietly because Americans are polite.

When we reached the far shore I was feeling semi-hypothermic and frankly a bit delirious, but I knew we had a long climb up to Green Gate awaiting us which presented a chance to refocus. As it turned out, Bowdy had navigated a whole series of setbacks to meet me. Initially my plan had been for him to go to Green Gate, but logistically it was simpler to meet me on the river’s right hand bank and begin his run with the crossing. This had proved a fortuitous decision as a forest fire near Green Gate had prevented many crews from accessing their runners earlier in the day. The resulting rush to meet runners at the river, though, meant there were long queues for the shuttle bus. Nervous he was going to miss my arrival time, Bowdy had elected to grab a handful of essentials from my crew bag and run down the fire road to the river crossing. He had got there a couple of minutes before I arrived.

I’ll be honest – there isn’t much I can tell you that’s of interest about the final 20 miles of this race. There are three reasons for this: firstly, the fatigue I was dealing with prevented me from taking much in; secondly, the darkness made it difficult to make out much beyond the few feet ahead of me; and thirdly, the trail is quite samey. I am sure to a local runner it’s a fantastic playground, but in the state I was in it just felt like we were constantly repeating ourselves, hitting the same switchback or crossing the same stream again and again.

The memories I have are out of sequence. I remember Bowdy’s freight train-like headtorch lighting up the trail for me; I remember leapfrogging with other runners as we all experienced our own internal surges and deflations, the 24-hour mark a carrot on a stick dangling just in front of us; I remember plenty of good chats with Bowdy about his career in the automobile industry and his love of adventure runs. But mostly I just remember the rutted out yellow trail in front of me, swinging left then right, up then down, never changing.

I don’t really remember which aid station in my memory corresponds with which on the list. I know that at Green Gate (or perhaps Auburn Lakes Trails) Bowdy advised me to drink some iced coffee, which really helped me refocus and regain some enthusiasm. I know that I did the same at Auburn Lakes Trails (or perhaps Quarry Road), only this time the coffee was hot and I couldn’t drink much of it. And I know that at Pointed Rocks (or somewhere else) Scott Jurek was wearing a plastic crown and I was so tired that I didn’t care that it was Scott Jurek.

But then, as I left Pointed Rocks, a sense of clarity began to return. Bowdy had to jog out to catch me as I had simply walked out on my own, determined to bring this thing to a close. My watch read 22 hours 18 minutes elapsed, with 6 miles to go. 100 minutes to run 10km. That felt do-able. The climb up to Pointed Rocks had been awful – the last pinch point on AJW’s list – but now there was nothing between me and the finish but runnable trail. Or so I thought.

In actuality, the descent from Pointed Rocks was quite treacherous. Even on fresh legs, it would be the kind of trail you take your time on, not wanting to roll an ankle or end up on your butt. With 95 miles in the legs, it was all I could to keep moving forwards. Technical downhills are my weak link; my legs were unstable and on more than one occasion I risked injury simply because I was trying to run it harder than I could manage. At one point, Bowdy reminded me to take it steady – “You don’t want to lose this thing in the last five miles.”

The trail continued in this fashion for what felt like an age, the famous No Hands Bridge failing to materialise despite the whoosh of traffic drawing achingly close. And then, suddenly, it was there, and we were running back across the American River and towards Robie Point at mile 98.9.

If anyone tells you it’s all downhill from the Foresthill, they’re lying. And if anyone tells you it’s all downhill from the river, they’re lying. And if anyone tells you it’s all downhill from Pointed Rocks – they’re lying. From No Hands Bridge to the top of Robie Point is a 3.5km run with 200m of climbing – that is a lot of climbing! Sure, it’s dwarfed by some of the climbs earlier in the race, but imagine climbing more or less to the top of Arthur’s Seat and you’ll have a sense of what Robie Point is like. It was a little bit soul-crushing to have come so far and still be faced with a climb like this. All I could think about was not letting the 24-hour finish slip away from me.

Slowly, though, the sound of music and cheering grew, and then lights became visible, and before I knew it somebody was yelling, “Welcome to Robie Point, mile 98.9!” and the trail became a road and Emily and Sierra were there waiting for us. We all started running together, and I thought, “This is it – I am running to the finish!” And then the road kicked uphill like an absolute bitch and I had to walk.

But then we started running again, downhill this time. There were no more hills. I passed a runner who I vaguely recognised from the previous few miles. “Well done,” I said. “We’re gonna do it, man!” he replied, and for a moment we linked hands and I felt him squeeze. It sounds weird but it’s a moment that stuck with me, a moment of solidarity between strangers.

And then I couldn’t quite believe it but the Placer High School came into view and there was the track and I was running on it. A woman was running alongside me filming on her phone and I realised this was being livestreamed. Either because I wanted to look good or I wanted it to be over sooner I picked up the pace and rounded the bend onto the home straight and then just like that the race was over. The race director put a medal around my neck and said “Well done” and we held each other’s shoulders for a second and locked eyes and I said “Thank you” and that was all I needed to say.

The Aftermath

Immediately upon finishing, I was a broken person.

My body had held up well throughout the race, but as soon as I finished I began to feel quite nauseous. Thinking about it, I probably ate upwards of 40 gels throughout the race, and whilst they’d all gone down well, I now felt as though some of them needed to come back up. I threw up multiple times and struggled to ingest anything other than a handful of plain crisps. After hanging around for an hour or so chatting with fellow finishers, we headed back to the hotel where I just about managed to shower before passing out. We then headed back to catch the final finishers, as well as a few heartbreakingly close DNFs.

We then awaited the official awards ceremony, where each finisher gets called by name to collect their buckle. It was ferociously hot – much hotter than I ever noticed it being during the race. I managed to nibble on some potato salad and crisps, though it took a while for my appetite to fully return.

In the end, I finished 101st, and 77th male. I overtook 91 people from Lyon Ridge to the finish, including, somehow, three people in the final mile from Robie Point to the finish. I knew my capacity to finish strong would serve me well, but there were a lot of moments where I genuinely thought I had let sub-24 slip. It was thanks to Sierra and Bowdy’s brilliant pacing that I was able to maintain a sufficient pace.

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what it is that makes Western States so special. It’s definitely not the course – don’t get me wrong, it is a brilliant course, but if you wanted to you could find dozens of routes that are more spectacular, hotter, harder, higher, you name it. You can even run most of the course anyway as part of the Canyons by UTMB event. And I don’t think it’s necessarily the exclusivity, either – UTMB is, after all, another bucket list race for many people, and yet is much, much bigger than Western States.

I think, just as with running – and life in general – it’s the people that make the difference.. Had the trail not been lined with spectators and supporters as we climbed the escarpment; had each aid station not been filled with dedicated volunteers taking care of my every need; had my pacers not been so intertwined themselves with the legacy of the race; had my fellow runners not been so honoured and humbled to be toeing the line; and had trail running history not been made by the elites up ahead then it all would have rung a bit hollow.

It was, to put it simply, a very, very special day, one that I’ll never forget.

If I am ever lucky enough to get back in, I will seize the chance.

One comment on "Western States Endurance Run"

Julie Scott

August 2, 2024 at 9:30 pm

It was a very special event that was the highlight of my Northern California trip with you and Emily. So extremely proud of you. Mum X

Comments are closed.