Taranaki: the Day the Mountain Won

Posted by Ed on January 6, 2020

This past weekend I attempted to climb Mount Taranaki, a 2518m (8261 feet) stratovolcano in the west of New Zealand’s North Island. Despite not reaching the summit due to inclement weather, I took a lot away from the experience, not least of which was a revitalised respect for the very real dangers one can encounter when traversing high mountain landscapes.

The day before my summit attempt, I caught an InterCity bus from Wellington to New Plymouth. In the final hour of the trip, the mountain loomed into view, and I must admit I was caught short by its sheer size. It stands in complete isolation, with a prominence of 2300m, dominating the skyline. It was not the first time I came to appreciate why this particular mountain plays a significant role in Māori mythology.

After checking in to my New Plymouth hostel Ducks & Drakes, which I highly recommend, I took a splendid walk through town and along the recently completed Coastal Walkway. On any other day, with its stunning views of the ocean and glimpses into the town’s industry past, the walkway would’ve been a trip highlight, but my mind kept being drawn back to thoughts of the mountain.

Though I’ve been trail running for five years this year, my mountain experience is still almost non-existent, limited only to a single day walk in Snowdonia with my friend Simon back in 2017, and a couple of hikes in Colorado and California whilst working in America. The highest peak I’d ever summited was the 1663m-high Ryan Mountain in Joshua Tree National Park, which doesn’t really count as the trail to the top only requires 350m of climbing.

As such, I made sure not to underestimate Taranaki, which has claimed 84 lives since records began and is New Zealand’s second most dangerous mountain.

I packed for the worst day I could imagine, short of injuring myself, which turned out to be a pretty good estimation of what was to come. I took three litres of water (the maximum recommended), far more food than I anticipated needing, a first aid kit, and multiple layers of clothing, including a hat, buff, and cap, for all conditions. I did not pack gloves which, in hindsight, was possibly my only mistake.

Warning Signs

I met a German girl staying at my hostel who was also hoping to summit, so we agreed to take it on together.

Some alarm bells started ringing when we arrived at the North Egmont Visitor Centre, the start of the hike, and were advised by staff that high winds and poor visibility meant we should consider taking on a different route, such as the mellower Pouakai Crossing. My German companion was not happy with the ambiguity of this suggestion, and demanded a ‘Yes or No’ answer as to whether or not we should try and reach the peak.

“I… can’t really answer that,” the guy behind the desk answered, somewhat flabbergasted. “I would advise you not to, but you’re responsible for yourself.”

I couldn’t have put it better myself.

Though conditions were certainly breezy, we decided that we felt safe enough to at least try and reach the Tahurangi Lodge, the start of the proper climb. From there we would assess what to do next, either continuing on up the mountain or taking the Poukai Crossing diversion around it.

Early on in the climb, we met a group of three walkers coming back down looking chipper but defeated. They had made it as far as the stairs above the Tahurangi Lodge before the winds had forced them to turn back.

They seemed pretty convinced that their decision was the right one, but they also looked a tad underprepared – one was in shorts, another had just a hoody on for warmth. With the wind supposed to die down later in the day, I wasn’t yet convinced that reaching the summit was impossible, but I made sure to remind myself that if at any point I felt unsafe, I was to turn back.

The walk up to the Lodge was fairly straightforward and mostly shielded by tree cover. Every now and then, we would round a corner and find ourselves exposed to the wind, which was only getting stronger the higher we climbed. The mountain above us was completely covered by cloud, and only the television tower by the lodge gave us any indication of how far we had to go.

At one point, the Summit Track grows significantly steeper for a few hundred metres, on a section known as The Puffer. I was pleased with my own level of fitness, my heart rate remaining low even on such steep terrain with four or five kilograms on my back, but my German companion was struggling somewhat already. She was by no means unfit, but I began to suspect that it would be unwise of her to continue past the Lodge, where the track grows more rugged and some low-grade scrambling is required.

Upon reaching the Tahurangi Lodge at 1500m, we were met by a Finnish couple and a South African gentleman (whose names I forgot to remember!) who were all debating whether or not to continue. We were now above the tree-line, and the wind was remarkably fierce, thrashing the grass around and occasionally forcing us to stand still and wait for a gust to die down.

In the end, my German companion decided she no longer felt safe, and elected to rest a while at the hut before turning off onto the Pouakai Crossing. Relieved of any responsibility I felt for ensuring her safety, I pressed on with the Finnish couple and the South African man. We were all more or less on a par fitness-wise, and it was exciting to feel like one of an experienced pack, rather than the stronger half of an unsure duo.

An Angry God

From the Tahurangi Lodge, the track enters into a rock-filled gully, where orange poles mark out the route to follow. This is the start of the true climb.

This gully is shielded from the wind, and I actually started to feel more optimistic about maybe reaching the summit. But as soon as we came out the other side and reached the wooden stairs, those hopes were somewhat dampened, as the wind came in sideways once again.

The stairs were the first part of the climb that truly felt like we were scaling a mountain. They were sufficiently steep that I got slight vertigo, feeling like the void was yawning behind my back. The cloud cover and poor visibility actually helped a bit here, as I was unable to see what lay below.

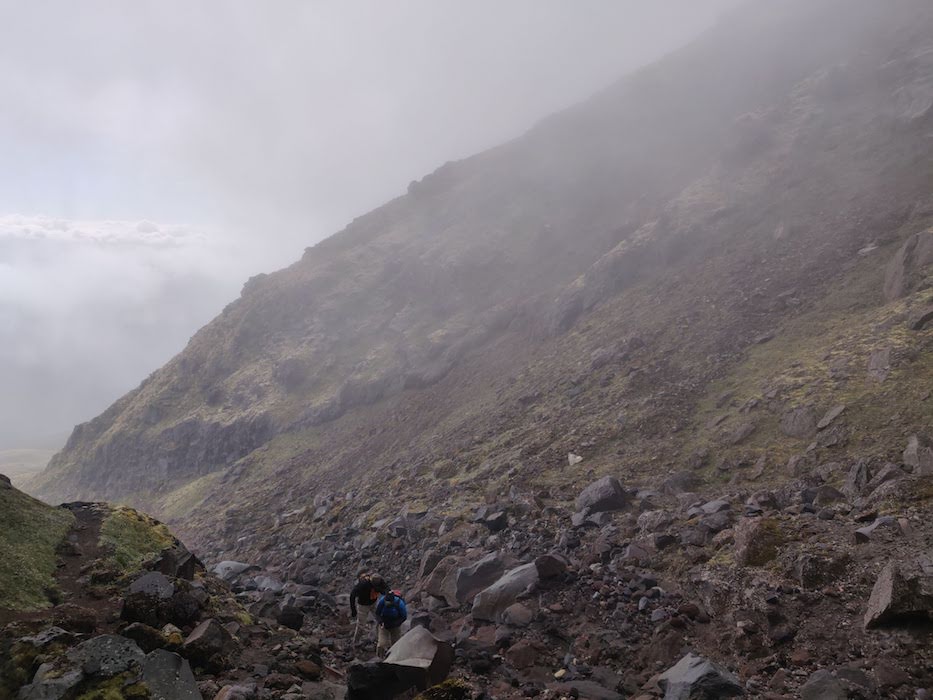

Though the wind was strong, the stairs meant that we had good footing and did not struggle to make progress. This all changed, though, when the track gave way to a scree slope that stretched up into the clouds. On a good day, this would be a taxing section, as the rocks were very loose and frequently gave way underfoot. In high winds, it was close to impossible, and things only grew more perilous the higher we climbed.

Here, again, I began to reflect upon the Māori’s mythological personification of Taranaki. It was remarkable just how much of a personality the mountain seemed to have, and how powerless we were as walkers when faced with the full force of that personality. Today, Taranaki was angry – and you don’t fuck with an angry god.

By this point my new South African friend – who was clad in three-quarter-length shorts and skate shoes, I might add – and I had surged ahead of the Finnish couple, catching up with two Kiwis who looked pretty comfortable. They had each summited a number of times, including in winter, and so I felt good hanging with them and knowing that their judgement was likely better than mine, though I made sure to pay attention to my own internal alarm bells.

On this scree section we encountered a number of walkers returning from further up, none of whom made it to the summit. A couple reached the top of the scree slope and encountered ice-covered snow which would require crampons to traverse. Most didn’t even make it that far.

We stopped for a few minutes and took shelter behind a boulder to eat some food and take a breather. My lack of gloves started to cause me problems – the wind chill was supposedly -15°C at the summit, and where we were resting it was certainly close to freezing, if not below it.

My fingers started to seize up, and though I had thumb holes in both my Inov-8 mid-layer and storm shell, I was forced to tuck them into my sleeves further to keep warm. Thankfully, this seemed to work, and I never felt like I was in danger of losing any digits.

Leaving the shelter of the boulder behind, I put on my North Face jacket, the last of my layers. Should conditions get worse, which they inevitably would, I now had no more protection that I could add. Hope of continuing on much further was beginning to fade.

We pressed on for maybe another half an hour before the Kiwis decided to turn back. By now, the windchill was feeling positively Antarctic, and on more than one occasion we were forced to plant a hand on the ground and wait out strong gusts. I would guess they reached around 80kph, based on the forecast for that day.

My South African friend and I waited for the Finnish couple to catch up, and together we pressed on for another 200m or so before stumbling upon a large boulder which made for an appropriate marker for the end of our climb.

We reached 1960m, and although the mountain was invisible above us, the thought of climbing another 550m was too much to bear. We had not yet even reached The Lizard, a technical rock formation leading to the summit that requires some scrambling. Traversing that in the winds we were faced with was too much like proper mountaineering, and not what we had come prepared for.

Turning Back

Despite doing exactly what I had said I would do – that is, reaching the point where I no longer felt like I could safely continue, and turning around – there was of course a sense of ‘Maybe’ once we began making progress on our descent. The scree field was hazardous and slow-going, but once we reached the stairs again, my mind inevitably began to speculate as to whether we were right to turn back.

Summit fever is a real and dangerous phenomenon, and as we descended and the temperature rose I had to keep reminding myself of just how severe the wind had gotten, and just how much I had not wanted to continue. At one point, I had sat down for a few minutes and found my mind completely blank. Taranaki is no Everest, but I feel like I got a glimpse into the kinds of mental battles mountaineers face when confronted with dangerous conditions.

We passed numerous walkers on their way up, all of whom asked us the same question we had asked those who came before us – ‘How far did you get?’ Some looked very prepared and skilled, others less so – a few minute after we turned around, a solo climber in denim shorts and a raincoat strode past us at an admirable pace. He looked determined, but I would be amazed if he made it much further than we did.

From what we heard, nobody made it to the summit that day. News reached us of an experienced climber who had hundreds of Taranaki summits to his name coming within 300m of the crater before turning back. He appears to have made it the furthest.

The Aftermath

The Tahurangi Lodge is technically members-only, but the handful of people staying there very kindly let us in to dry off and warm up a bit. We had some tea and exchanged stories for a while before splitting up to fill the time now available to us – it was only 11 AM by this point, after all.

Conditions were still windy, but significantly warmer this far down the mountain. I elected to walk back to North Egmont via a section of the Round the Mountain track, which slowly descended back beneath the tree line and offered occasional glimpses of the angry mountain above.

It was a pleasant walk through classic New Zealand alpine terrain, and at least partially made up for the aborted summit attempt. I haven’t done enough tramping (as Kiwis call it) here in New Zealand, so it was nice to stroll along an easy route and take in the stunning views. It certainly gave me plenty of time to process the experience.

What struck me most was just how dramatically conditions can change at altitude. Walking around the mountain, I gradually stripped down to just my technical T-shirt, but just a few hundred metres above me the mountain was still shrouded in clouds, and the sound of wind rippling against my hood was still ringing in my ears.

Whilst I am of course gutted to have not made it to the top, I do think that I took more from the experience than I would have had conditions been more ideal. I learnt what it’s like to swallow one’s pride and prioritise safety over any half-baked notions of ‘glory’. I learnt that, despite always considering myself a runner, I am more interested in all-round mountain athletics than I previously thought – the ancient peaks of my home country, the UK, now glimmer with a potential I was previously unaware of.

And, most importantly, I learned the true meaning of John Muir’s apocryphal line: “You don’t ever conquer a mountain. You are permitted to stand on it.”

Taranaki, at least that day, was not in a favourable mood.

I thought for a while about rescheduling my bus back to Auckland and trying again the next day, a Sunday, but the forecast predicted it to be even worse, with winds up to 100 kph.

The next potential summit day looked to be Wednesday, when the wind was only forecast to be 30kph, but given that it was going to snow on Tuesday, I didn’t want to spend all that money on accommodation only to fail once more due to icy conditions. Especially given that next Saturday I’ll be completing a 45km adventure run in Tongariro with some friends, and want fresh legs for that. In the end, the experience I had was its own justification, and I didn’t want to tarnish it with a half-baked second try.

A few weeks prior to my summit attempt, I had bought a print made by a local New Zealand artist depicting the mountain, intending to frame it when I return to the UK.

It will now have a very different meaning – reminding me of the forces nature is capable of unleashing, and softly nudging me towards one day returning to New Plymouth, and having another go.

For now, onwards.