Riverhead Relaps Backyard Ultra

Posted by Ed on May 5, 2019

The Riverhead Backyard Relaps Ultra, hosted by the good folks at Lactic Turkey, consisted of around 50 runners from all over the country, and some (like me) from further afield, drawn by the opportunity to compete for a Golden Ticket entry to the 2019 running of Big’s Backyard Ultra in Tennessee. At least, some of them were — for me, I just wanted to experience this novel approach to racing, and to see how far I could go. It was a bizarre and mind-altering experience, and one I could not help but remain fascinated by after it had ended.

Race director Matt delivers some words of advice to the doomed.

On Friday at midday, after pitching our tents and setting up our various food and gear supplies, we all lined up at the start to begin the first loop. Spirits were high and nerves were lax — it all felt so cheerful, so modest. What was 4.17 miles an hour, after all? Jogging pace, for many of us. Less than that. And indeed, 50 minutes later I comfortably strolled back into camp, feeling fresh and optimistic about what I might achieve that day. I lay in my hammock, snacked on some M&Ms and fruit, and tried to get some rest.

And then, the whistle blew. Three minutes to go. Somewhere, deep in the pit of my stomach, something began to worry. “This could get ugly”, I thought. And then I tried not to think anymore.

The first few metres of the Riverhead Backyard Relaps Ultra course.

The Format

The backyard ultra is a novel way of staging a race. At first it appears to resemble the familiar loop-based format— runners must run a 4.17 mile loop as many times as they can. The key difference here, though, is that when the runners finish a loop, they must wait for the clock to tick over to the next hour before they begin the next one. Thus, every hour, on the hour, all the remaining runners start a new loop together. All are tied for first place, and whether they finish the loop in 30 minutes or 59, all are still in contention for the win so long as they start the next loop. Nobody is ahead of anybody else.

The 4.17 mile distance per loop is such that runners complete 100 miles with the passing of every 24 hours. Anybody who finishes a loop over 60 minutes, or is unable to start the next loop, is automatically counted as a DNF — Did Not Finish. In the end, only one person will count as a finisher — he or she who is able to carry on racking up loops until nobody else is left. It’s a simple matter of being the last person standing.

The ingenuity of this approach is hard to overstate. Faster runners carry no advantage over slower runners, except for maybe being able to take more time in between loops to rest and recover. Instead, pure endurance is given centre stage — as long as you can maintain a pace faster than 4.17 miles per hour (which is, as Gary Cantrell, the inventor of the format, no doubt intended, painfully manageable), you can stay in contention for the win — but you may have to wait for quite a while. In October 2018, Johan Steene of Sweden won Cantrell’s original backyard ultra, named Big’s Backyard Ultra after Cantrell’s dog Big, by running 68 laps in 68 hours, or 283.3 miles.

Back to the Race

Loop two. Here were are again. The same faces, the same course, the same splits. Here there were no ‘elite runners’ far off in the distance, no ‘mid-pack’, no ‘back of the packers’. All of us were in exactly the same place — 1st. Those guys up ahead? They’re in 1st place. Those guys behind me? They’re in 1st place. Me? I’m in 1st place. My mind began to swim in the strangely flat time of the backyard ultra.

On loop three my comprehension of what I was experiencing started to slip away. Rarely if ever do I run for three hours recreationally, and so it makes sense that beyond this point normality began to seem a distant memory. I found it hard to believe that I had been out here for three hours. The course became uncomfortably familiar, yet also seemed different each time as the day passed and the light changed.

The loops began to simultaneously speed and crawl by. At the start of each lap, as we all lined up again, I felt like I was stuck in a state of permanent deja vu. The various segments that differentiated the course seemed to be both stretching out and compressing — the muddy path, the white forest, the gravel road, the big climb, the steep descent, the small climb, the technical forest road, the grassy single track, the finish line bunting. Each lasted forever, yet each time I came to the finish line I was met by the same sense of relief at the ease with which I had completed the course.

My splits all hovered around the 50 minute mark, giving me a reasonable window in which to rest and recover, yet a window which began to noticeably shrink all the same. The race became a wave in which I was caught, trying to keep my head above the water, increasingly unable to stay on top of simple things like hydration, nutrition, and electrolytes. The 3-minute whistle became a call-to-arms, a triggering alarm that promised to plunge me back into a little slice of hell, if only for 50 minutes. I tried to talk to other runners during the loops, to keep the chaos at bay. It worked for a bit. But in the end, I succumbed.

On loop 7, the first loop to be run fully in the dark, something within me gave out. I kept pace with a couple of stronger runners for the first mile or so, but when we hit the long, gently climbing gravel road once more, I started to walk, and I began to ponder the warmth of my tent, the food I had packed, and sleep. It dawned on me that it was possible to escape from this crazy merry-go-round without end, and as the loop progressed I became increasingly certain that I wanted out.

The beauty of the backyard ultra, its raison d’être, in fact, is that it guarantees failure for all but one runner. A DNF is to be expected — it’s simply a matter of when. By removing the time constraint on the race as a whole, it becomes an open-ended medium in which you, the runner, can (and will) discover your limit. Out in Riverhead Forest, on my own in the darkness, I realised that I had found out what my mind would do that day. It wasn’t as far as I had hoped, but it was the reality I was being confronted with. And that was okay.

Perhaps it was the darkness, perhaps it was my stomach, perhaps it was my mind. It was probably all these things. I made some fatal nutrition mistakes early on which, even after being gifted some electrolyte sources in the form of chicken stock from a kind American runner, came back to haunt me in the end. I didn’t get a good night’s rest the night before (how could I?)

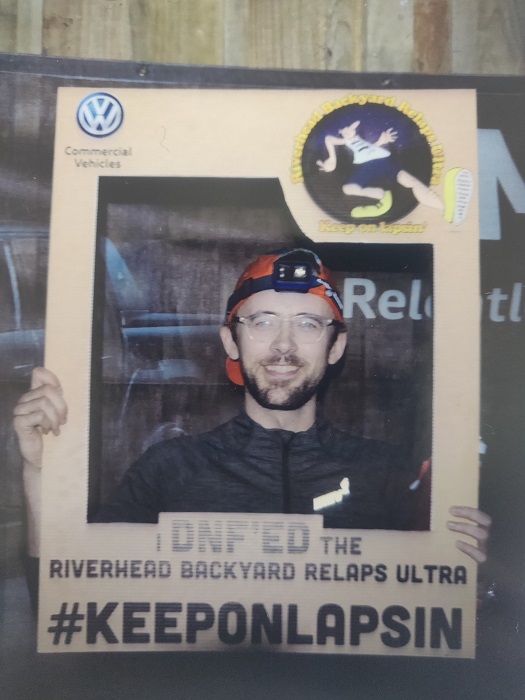

But as I crossed the timing mat at the end of loop 7 in 58:30, with 29 miles under my belt, I knew there was nothing left to do. A marshal encouraged me, “At least start the next one!”, but there was no chance. I had had an experience that justified 7 hours of suffering and brought my race to a satisfying close; I did not want to rage against the dying of the light, not today. I was done, and I was okay with that.

Failure is inevitable.

It’s the nature of the beast that, as impressive as 7 hours of running might sound to the uninitiated, by the time I dropped out the race had barely gotten started. As I lay in my tent and settled into a kind of half-sleep, I was occasionally awoken by the devilish 3-minute whistle sounding, and reminded of those runners still out there, stuck in that hollow, flat timescape. Morning rolled around, and I stumbled out into the light, stiff-legged, to get a coffee and some breakfast from the catering vans. It was 9am, the race had been going for 21 hours, and still 5 runners remained.

I can’t really comprehend the mental and physical fortitude it takes to run 4.17 miles every hour, on the hour, for a whole day. The individuals who lined up at the start of each loop on Saturday seemed to me to be superhuman. Don’t get me wrong — their stiff gaits and grim smiles betrayed their suffering. They looked broken. But they were still chatting, still making sense, still calmly instructing their crew about what food they needed and what gear needed changing. They were sentient and self-aware and focussed, and started each lap together in a kind of begrudged camaraderie. After all, between them they were carrying the very prize that was dragging them forward. Amongst them stood the sole finisher; they just had to figure out who that was. The finish was a constantly receding line just ahead of them.

A second day of running commences as the fab five start lap 25.

Eventually, after 26 hours of running, only two runners remained — Christchurch’s Adam Keen and Blenheim’s Katie Wright. Adam finally surrendered after 28 hours, or 116 miles, leaving Katie to complete one more loop on her own and be crowned the victor. Instead, she chose to run two, so as to reach a total of 200km of running in 30 hours. Her remarkably consistent splits — all hovering around the 52 minute mark — combined with her sunny, cheerful optimism all served to make her a deserving winner. (That’s another interesting feature of the backyard ultra — when it comes to endurance over ultra-long efforts, women have consistently rivalled men. Not only is time itself flattened out by the format, but so are any athletic disparities in gender.)

It’s an inherent part of the structure of the backyard ultra that the winner is the only runner not to reach their limit. Katie’s 30 loops were defined not by her limitations but by the limitations of her competitors, most notably Adam Keen. Had Keen kept going, Katie would have been forced to join him or surrender. As such, Katie’s prize of a Golden Ticket to Cantrell’s event in Tennessee — along with the winners of 9 other backyard ultras around the world — is another ingenious plot by Cantrell to generate a truly world-class field, and bring together runners who might spur each other on into the uncharted territory of running over 300 miles. Lord knows what incomprehensible distances might be achieved in the years to come as this format finds its star athletes.

Now it’s a few days later, and I am happy to say that I have slipped back into a sense of time much more in alignment with my normal experience. But I would be lying if I said that I didn’t miss the place that the Riverhead Backyard Relaps Ultra took me to. My world was briefly reduced to just the track ahead of me, just the loop I was running — the same loop I had always been running, and maybe always would be. It was both a sense of nothingness and of the infinite, an experience that, had I persisted, would likely have bubbled over into an almost psychedelic reworking of my perceptions. One day I hope to experience it again — and for longer than 7 hours, at that. Until that day, I’ll stick with my usual weekend long run.